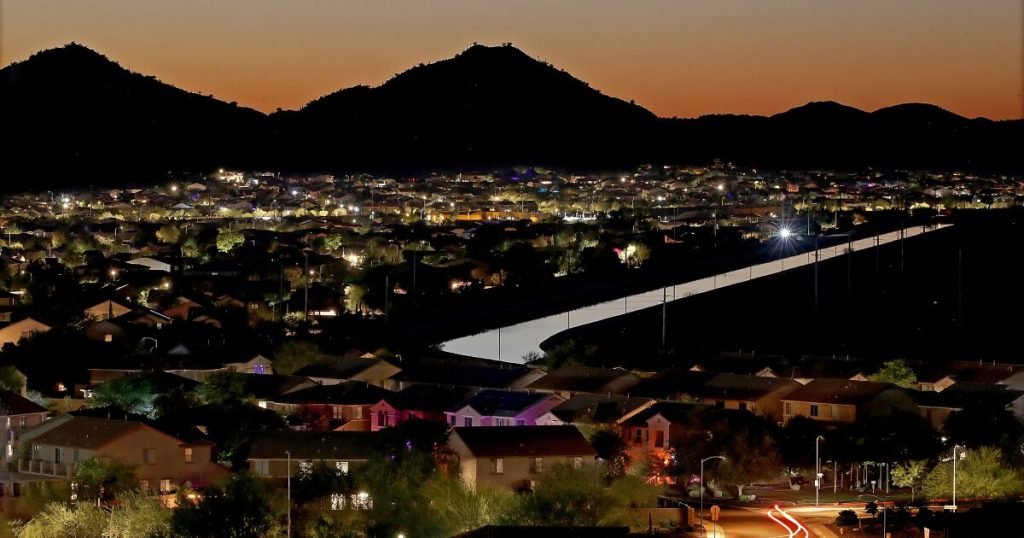

Arizona governor plans to limit new construction in parts of the Phoenix area after state analysis found there wasn’t enough groundwater to support all planned growth over the next few decades announced.

Governor Katie Hobbs’ announcement Thursday represents a major shift for one of the nation’s fastest-growing metropolitan areas, with some suburban development emerging in the desert surrounding Phoenix. is expected to hinder

State officials have analyzed the groundwater in the Phoenix area and determined that the area’s groundwater is not sufficient to supply all of the expected water demand over the next 100 years. As a result, Arizona’s water regulator will stop issuing approvals for new developments in areas that rely entirely on groundwater pumping.

the governor announced the result study The Arizona Department of Water Resources found that the Phoenix area will have an “unmet demand” for groundwater supplies over the next century.

“This study shows that we need to act again,” Hobbes said at a news conference. “If nothing is done, we could run short of 4% of our groundwater supply over the next 100 years.”

The announcement comes as Arizona is also working to cut its water supply from the Colorado River. The Colorado River is over-allocated and has been depleted by more than two decades of drought exacerbated by climate change.

Phoenix and surrounding cities depend on a variety of water supplies, including water from the Colorado, Salt, and Verde rivers, and water pumped from wells. In recent years, suburban areas such as Queen Creek, Apache Junction and Buckeye have grown rapidly, relying primarily on groundwater.

“We must fill this gap to find efficiency in water use, manage aquifers wisely, and increase the use of renewable resources,” Hobbs said, referring to imported water from the Colorado River and elsewhere. bottom.

Groundwater is regulated around Phoenix, Tucson, and other cities under Arizona’s Groundwater Control Act of 1980, which requires developers to obtain water permits that demonstrate long-term water availability.

Hobbes said the state will “suspend approval of new secure water supply decisions that rely on groundwater pumping to avoid increasing future deficits.”

Hobbes stressed that the new restrictions will not affect industrial development or the construction of projects already certified by the Ministry of Water Resources. He said there are about 80,000 homes that have yet to be built.

“This suspension will not impact growth in major cities where robust water portfolios have proven to cover current and future demand,” Hobbes said.

Hobbes, a Democrat who took office in January, has said he wants better management of groundwater and recently set up a council to consider reforms. She recently published the following state analysis results: showed that groundwater is inadequate This is to support planned growth in the Hassayampa area west of Phoenix, where large-scale developments that rely primarily on groundwater are proposed.

Water experts said the governor is making important and necessary changes.

“Groundwater is the real key to the long-term sustainability of desert cities like Phoenix,” says Jay Famiglietti, a professor and hydrologist in the Department of Sustainability at Arizona State University. “So everything we do in the future to save water will be very important, not just now, but for future generations.”

He said the governor is moving towards a comprehensive plan that also includes conservation, searching for new water sources, exploring technical solutions and ways to improve policies.

“She is providing the necessary leadership in this context of rapidly changing climate and declining groundwater availability,” Famiglietti said.

Kathleen Ferris, a researcher at the Kill Water Policy Center at Arizona State University, said she has been pushing for this kind of change for years.

“We’re in a situation where we can’t use groundwater to expand the lot any further,” Ferris said. “In order for us to grow, we must grow sustainably.”

State officials and others said the change would not stop growth.

In most cities and suburbs around Phoenix, new developments can be made within the jurisdiction of a water utility that has an approval called a Secure Water Designation. Planned subdivisions that have already obtained certificates of approval will not be affected.

In other areas, however, proposed subdivisions will not be permitted unless the developer can demonstrate adequate water supply for 100 years without relying on local aquifers.

“There will be growth, but this will change the pattern of growth, the density of growth and where it is likely to occur,” said Ferris, former director of the state water resources agency.

“With limited groundwater, we can’t continue to grow. We can’t do that, we can’t live sustainably in this valley and this desert,” Ferris said. “We have to learn to live within our means. We have to adapt and make changes.”

Business leaders also expressed support for the governor’s and water authorities’ actions. Chris Camacho, chairman and chief executive officer of the Greater Phoenix Economic Council, said that by proactively addressing these challenges, “we are committed to long-term sustainability and the future of Arizona’s water.” It shows a dedication to security,” he said.

This isn’t the first time state officials have reassessed the amount of groundwater needed for growth. In 2019, the Department of Water Resources stopped approving new housing developments in parts of Pinal County between Phoenix and Tucson. Forecasts showed a shortage of groundwater to meet long-term demand.

The latest measures were adopted according to the new groundwater model developed by the ministry.

The model results turned out to be consistent with past models and “more or less what we expected,” said Emily Rodolce, manager of the agency’s Groundwater Modeling Section.

Ryan Mitchell, the agency’s chief of hydrology, said the recent surge in development projects could also swell projected groundwater demand.

“We need to incorporate massive pumping into predictive simulations that exceeds what has been historically pumped over the last 10 or 20 years,” Mitchell said.

Current projections combine historical demand using water records through 2021 to account for all water certificates issued for proposed developments (including those that were not ultimately built). It is based on adding “unmet demand” to

“The reason we have to consider all of them, even if they haven’t been built yet, is to protect the consumers who live in those homes,” Mitchell said.

Based on current forecast models, state officials calculated that the Phoenix area will use 140 million acre-feet of groundwater over the next 100 years.

They estimated the unmet demand for that period at over 4.8 million acre-feet. (An acre-foot is enough water to supply about 3 typical homes in the Southwest at average annual water usage.)

The good news, Mitchell argues, is that demand can change, and if demand declines when the next forecast is calculated, the 4% gap between projected supply and demand can be eliminated. It means that it can help fill in.

“As the data changes over time, let’s say next year the current demand usage is different, and then we can run the model again,” Mitchell said.