Weeks before California lawmakers left Sacramento for their summer recess, more than a dozen environmental bills died in the Democratic-controlled state Legislature due to strong opposition from business leaders.

One bill would hold oil companies responsible for respiratory illnesses in children living near oil drilling sites, another would ask California voters to declare a “right to clean water and air,” and would divest fossil fuels from public employee retirement funds and ban state agencies from buying plastic bottles.

Lawmakers say there are a number of factors that led to the bills' deaths. $45 billion budget deficitFor example, several lawmakers could be absent due to contracting COVID-19 just before a key deadline.

But there was another common thread: The industries that opposed these bills had a history of financially supporting moderate Democrats in Congress, either through campaign contributions or donations to politicians' favored charities.

Over the past two election cycles, Chevron has spent about $10 million on California elections, according to Secretary of State data. Valero spent another $3.9 million, and Marathon Petroleum spent $3.3 million, according to the data. A quarter of its contributions to congressional candidates went to Democrats, and millions more went to committees that support Democrats.

These companies also regularly make charitable donations at the request of politicians, which can also be a way to garner support from politicians. Between 2021 and 2023, Chevron, Marathon Petroleum, Calpine, Phillips 66 and the Western States Petroleum Association gave a combined total of more than $800,000 to nonprofits at the request of state legislators, according to data from the California Fair Political Action Commission. More than half of this money came from Chevron, which donated more than $440,000.

“When big money moves in politics, it blocks legislation. It maintains the status quo. I can tell you that this is not good for California,” said Rep. Steve Bennett (D-Ventura), whose bill to limit plastic purchases was among those quietly killed in May after failing to get a vote by a crucial midyear deadline.

In June, Rep. Isaac Bryan (D-Los Angeles) Constitutional reform was shelved He vowed to give Californians a right to a clean environment and to reintroduce an improved version next year. The Petroleum Institute opposed it, and the California Chamber of Commerce board Lawmakers, including executives from Chevron and other energy companies, have denounced the bill as a “job destroyer,” a label that often hampers support from pro-business lawmakers.

Also in June, Sen. Lena Gonzalez (D-Long Beach) announced she would not move forward with a bill to divest public employee retirement funds from the fossil fuel industry. SB 252 faced strong opposition from the oil industry and was not supported by several moderate Democrats on the Senate floor. Gonzalez said in a statement: Decision to put the bill on hold This is because the committee's amendments were intended to weaken it.

In a Legislature generally known as one of the nation's most progressive, where Democrats hold a supermajority and climate change is a priority, moderate Democrats could be a key swing vote that will determine how far California moves left. Environmentalists see Democrats as beholden to the corporations that back their campaigns, while business leaders see moderate Democrats as a balancing force in a Legislature where one party holds all the power.

“The middle class is really important to policy,” said Kevin Slagle, vice president of the Western States Petroleum Association, which lobbies for oil companies in Congress.

“They play a key role in making sure policies don't go too far one way or the other.”

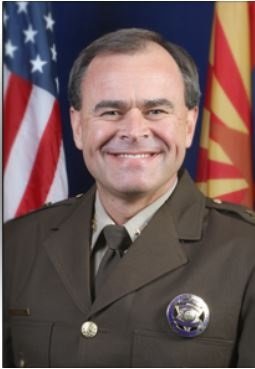

California Assemblywoman Blanca Rubio leads the moderate Democratic caucus.

(Rich Pedroncelli/The Associated Press)

Slagle said the petroleum association opposes many environmental bills because of concerns about rising energy costs, even though California has been aggressive in its transition to clean energy. Remaining It is one of the leading oil producing states in the country.

The industry found an ally Senator Blanca Rubio (Democrat, Baldwin Park) Leader of the Moderate Democrats, a loose group of lawmakers who sometimes side with Republicans to crush progressive ambitions.

Oil companies and industry groups have given Rubio more than $200,000 over the past eight years, according to state campaign finance data, making him the top oil-related recipient of any incumbent during that time, beating the runner-up, Tim Grayson (D-Concord), by about $40,000.

“She's very smart, very competent, and she really understands environmental issues and how they affect ordinary people,” Slagle said of Rubio. “Not only does she understand a lot of the policy goals, but she also understands how those policies actually affect people's lives.”

Environmentalists say Rubio votes in the interests of his big oil donors, while climate change advocacy groups give him credit for supporting climate-friendly legislation. California environmental groups have called Rubio 33% For the 2023 legislative session, her approval rating has fallen to 83%, down from 83% in 2017, her first year in Congress.

“The average Democrat who received oil money has a score of 66 percent,” said Melissa Romero, legislative advocate for California Environmental Voters. “The average Democrat who didn't receive oil money has a score of 96 percent, an A. It really shows how much oil money has influenced the environmental voting record.”

“For Blanca Rubio, one of the Democrats most heavily funded by the oil industry, the correlation couldn't be clearer,” Romero added.

Rubio did not answer questions about his voting record.

The bill, which Rubio did not support, proposes a variety of environmental protections, many of which target the activities of California's oil industry.

In 2022, she refrained from voting. SB1137The bill passed, banning new oil drilling near schools, playgrounds and residential areas.

That same year, she withheld her vote on SB 260, a bill that would have required large corporations to disclose information about their carbon footprint. The bill failed, but SB253 It passed last year, but she did not vote in favor of it then either.

She also AB1167A major oil company has a well that is almost fully drilled, AB631The bill would increase penalties for violating state oil and gas regulations. Both bills passed.

Rubio's ties to big oil companies also help her raise money for her annual Thanksgiving charity event, Operation Gobble. Last year, she raised enough money to deliver more than 1,000 turkeys to families in the San Gabriel Valley. Chevron and Valero They each donated $5,000.Rubio reported raising $124,000 for the event.

Asked about donations made at a turkey giveaway in West Covina last year, Rubio noted that it benefited voters.

“I never miss an opportunity to ask,” she said, “and I ask because my community needs it.”

Cars lined up more than a mile long and waited hours to receive free turkeys in bags emblazoned with Rubio's name, a way for Rubio, who has represented the district since 2016, to not only give back to the community but also to boost his own image.

Earlier this year, she faced off in the primary against a left-wing challenger, West Covina Mayor Brian Tabatabai, who said Rubio had not done enough to address climate change, the housing crisis and the plight of public schools.

But the California Democratic Party endorsed Rubio in the race, and she won by a large margin, receiving more than twice as many votes as her Democratic opponent. Tabatabai said Rubio's name was well known in her district and called her turkey giveaway a “PR event.”

“I don't see this event as addressing the needs of the community,” Tabatabai said. “It's a way to brand and promote her name.”

Rubio said soliciting charitable donations from lobbying companies is a way to help his constituents, and he acknowledged that donors may have other motives. Chevron reports its turkey donations in its reports, as do other companies that make charitable donations at the request of state lawmakers. Lobbying Disclosure As an official “reward for influence”.

“Of course, they want to be on my side,” Rubio said. “It's all political. Once they understand that, they know where they stand and I know where I stand. So I say, 'Hey, give money to charities that will help me do all this.' That's the way it should be. I mean, it's all about relationships.”

Fitzgerald and Harrison Caldwell are freelance journalists who began covering this story while enrolled in Berkeley Journalism School's investigative journalism program.