Mammoth Lakes, California — If all the Mexican-born service industry workers in this vibrant resort high in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains took just one day off work and stayed home, the tourism economy’s booming economy would likely be on ice. It will be more difficult than a first-time skier skiing an expert slope.

Residents said most restaurants would be without staff. Hotels and Airbnb will suffer the same fate. Construction projects across the prestigious ski area will come to a grinding halt.

“I think it’s like a zombie movie,” said Jose Diaz, 33, a Sinaloa native who is a supervisor at Stove, a cozy breakfast spot in the center of town.

Like many who come here from small towns in Mexico, Díaz didn’t come here for the skiing. He had heard through word of mouth that Mammoth was a good place to earn a steady paycheck.

Mammoth Lakes restaurant kitchens and hotel break rooms are buzzing with the idea of Latino workers going on a one-day strike to demonstrate the town’s dependence on imported labor.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

That was 14 years ago. Now, Díaz and his wife, who is from Guadalajara and met while working at Mammoth Restaurant, say they are both here legally. They have two U.S.-born children and recently bought a condo in town.

But like most people in this alpine community of about 7,000 people, they are at risk if President-elect Donald Trump’s declaration to deport millions of illegal immigrants comes true. I have friends and family who will be exposed.

Local residents are wondering how they should specifically respond. Some workers say they hope Trump will be more flexible when it comes to resorts like Mammoth and South Lake Tahoe, given his business history.

Some are calling for more proactive efforts. Restaurant kitchens, hotel break rooms and group chats are buzzing with the idea of Latino workers going on a one-day strike to demonstrate the town’s dependence on imported labor.

Mayor Chris Bubser said he sympathizes with the growing fear over deportation, but hopes a strike doesn’t materialize.

Mammoth Lakes residents argue that mass deportations of undocumented workers, who provide much of the labor force, would wipe out the resort.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

“I feel bad for the business owners, because they’re not the ones making these terrible threats. They’re going to be left alone,” Bubsar said.

As state and local officials across California grapple with the potential impact of President Trump’s deportation proposal, attention is understandably focused on the rural areas of the Central Valley. About half of the people working in the fields and orchards there are believed to be illegal immigrants.

But more expensive ZIP codes are also vulnerable, and it’s hard to imagine any part of the state that would be hit harder than Mammoth Lakes if a significant percentage of undocumented workers suddenly disappeared.

That’s because most of the tourists who flock to this internationally famous resort are white-collar professionals. And the people who own real estate are generally real estate investors, skiers with enough money to afford a vacation home, or wealthy retirees heading for the hills to escape the crowds of coastal cities. It is us. No one will respond to an ad asking for help as a cook or snowplow driver.

As a result, immigrants will take on the bulk of the labor.

Workers move lumber at an apartment construction site in Mammoth Lakes.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

About one-third of Mammoth’s population is Hispanic, and more than half of the students in local public schools come from Spanish-speaking families, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

Many of the town’s Latino residents are citizens or green card holders, and some come from families that have lived here for generations. But residents estimate that at least half are in the country illegally. It’s not difficult to find.

On a recent chilly afternoon, about half a dozen men were clearing snow from a commercial office building in town. The roofing company owner asked to be identified only by his first name, Julio, because he is in the country illegally. He said he has been doing construction work in the U.S. since 1989, most of it in Mammoth Lakes.

His company has 15 employees. He also has three children, all of whom are U.S. citizens. His oldest is a California Highway Patrol trooper.

He doubts the merits of a one-day strike by Latino workers. “The purpose of the strike is to show that we need Hispanic workers, but I’m sure everyone already knows that,” he said with a shrug.

Last week, Julio took on roofing work at a site in Mammoth Lakes.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

He cited record snowfall in the winter of 2022-23, when homeowners were scrambling to clear snow from their roofs before their homes collapsed.

“I had never seen so many Americans, white people, on the roof,” Julio said.

He said he’s not too worried about the deportation story, in part because he doesn’t think there’s any point in stressing about something you can’t control. But he also said he believes Mr. Trump is a rational businessman and must know how much of an impact undocumented workers have on the economy.

And President Trump is building, Julio joked, “I’m sure he’s hiring some illegal aliens for him.”

In fact, Julio thinks Trump is a “pretty good president,” even though she was offended by the sweeping and disparaging comments Trump made about Mexicans during the campaign. Julio said he was correct in deporting people who cross the border illegally “in search of free things.”

“I’ve been working hard,” Julio said. “I pay for all my medical bills, dentistry, and vision out of pocket. I didn’t rent low-income housing because I didn’t think I needed it.”

He said he hopes Trump will save hardworking workers like himself who “make our country stronger.” But he’s fine with deporting lazy people.

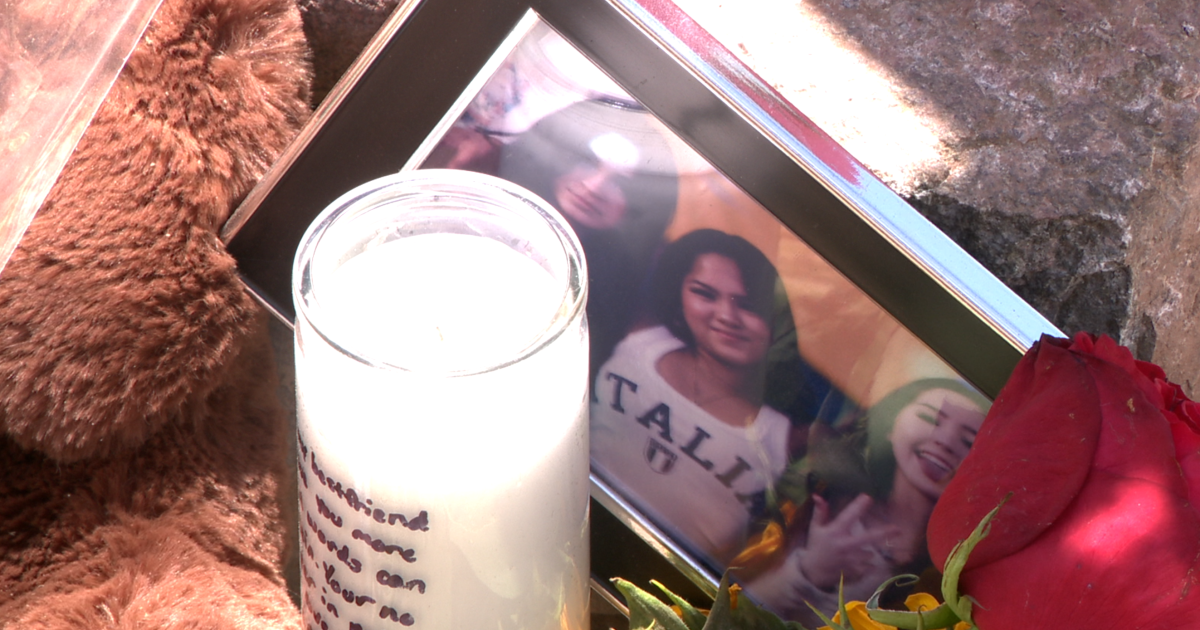

Kitchen workers at a popular Mammoth Lakes restaurant take a short break for breakfast.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

“Those who do not benefit the country should be removed from here,” he said.

For others, the shocking breadth of President Trump’s threat to deport up to 11 million illegal aliens may be frightening. It is difficult for them to imagine how a dragnet of that scale can pause to consider the merits of individual cases.

The secretary at Mammoth School only asked to be Maria, but she is one of the people she worries about.

She said she came from Mexico with her mother as a child and has since been granted U.S. citizenship. However, her husband has worked in construction in Mammoth for more than 20 years and is in the country illegally.

He was caught crossing the border illegally when he was 14 and has not been able to “adjust his status,” he said.

Maria and her husband have three children, all born in the United States, and one of them is planning to join the military soon. However, children are increasingly anxious as they follow the news and listen to gossip at school.

“My 10-year-old daughter is scared because the new president has said he will deport everyone,” Maria said.

Her husband works in construction, works as a bus driver for the school district, and recently started his own snow removal business. He has an Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITN), a document issued by the Internal Revenue Service to foreign nationals (including illegal immigrants), so foreign nationals can pay taxes just like everyone else. can.

“He is a responsible, hard-working person with no history of ugliness,” Maria said.

Mono County Sheriff Ingrid Brown worries that crime victims will be unable to seek help for fear of federal immigration agents.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

A few years ago, his kidneys began to fail. Thanks to health insurance from Maria’s job at the school district, he was able to undergo dialysis and eventually receive a transplant. But now he relies on very special medications to survive, Maria said.

Maria worries that if he is deported and has to return to his hometown in Michoacán, he will not be able to get life-saving medicine.

“People are dying from things like that in Mexico,” she said.

Like many law enforcement officials in California, Mono County Sheriff Ingrid Brown said she would not help deport illegal aliens. But she worries that people will be too afraid of federal immigration officials to turn to her for help if they are robbed, assaulted by a boyfriend, or otherwise victimized. There is.

“If they’re worried they’re going to be deported or separated from their children, they’re not going to call,” Brown said.

Brown said he is skeptical that a roundup will actually happen at this point. “I don’t think they had a plan. I think it was all a bunch of stories,” she said.

Even if federal agents show up, they can’t stop it, but news travels quickly in small towns, and outsiders who don’t know the local situation have a hard time catching up with locals who almost certainly do. she said. They were coming.

Mammoth High School students walk home at Mammoth Lakes after school.

(Brian van der Brug/Los Angeles Times)

She also thinks the disruption to the economy will be so severe that immigration officials will likely get little cooperation from the rest of the city. In any case, most people here are dependent on immigrants.

“People think resorts like Mammoth are just for rich people to play,” Brown said. But it’s immigrants who do all the work and keep the industry “booming.”