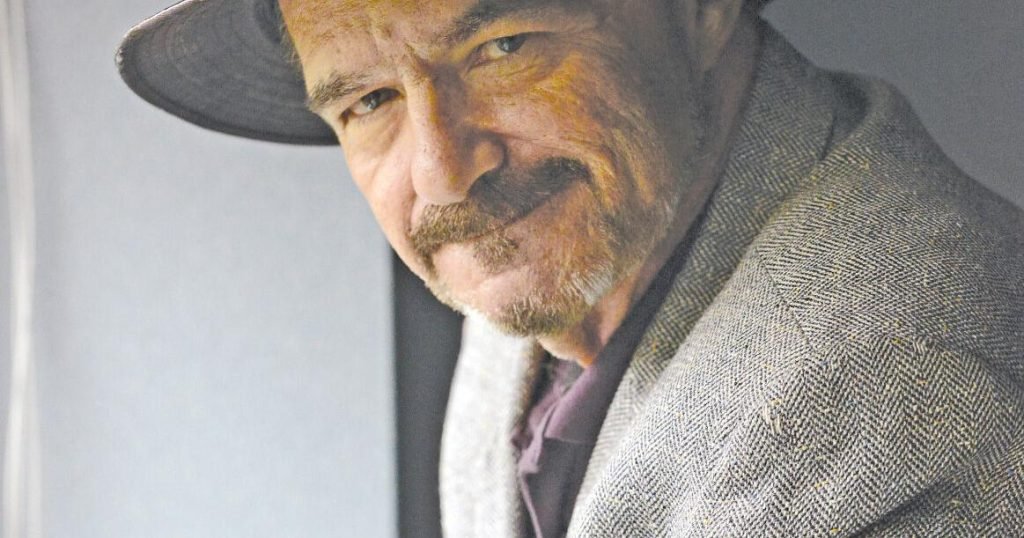

Craig Weaver, the son of a railroad worker in Cresson and a successful businessman, regrets the years he spent as a drug addict.

His addiction began when a 19-year-old student was playing tackle football with members of his fraternity at Indiana University in Pennsylvania.

It wasn’t a friendly game between the “brothers” when a 250-pound lean, highly athletic running back slammed into him, breaking his femur.

Weaver, a communications and journalism student, came out of the hospital after three months in tow and a full body cast.

He had also developed a full-blown addiction to painkillers.

Over 30 years of addiction eventually led to his heroin abuse, a failed business, a toll on his health and, most unfortunately, the abandonment of his wife, son and daughter.

“I was becoming an animal. Below an animal. Animals still take care of children,” he said in a recent interview.

He knew heroin was destroying his life, so he had to move away from his family because he didn’t want to subject his children to dysfunction.

Weaver, who graduated from college after recovering, responded to an ad for a driver for a steak and seafood delivery business and found him to be a pretty good salesman.

He eventually started his own meat delivery business.

One of his customers was a jeweler. Weaver began consigning jewelry to the homes of wealthy clients, which led to his show at Home, where he was able to make thousands of dollars in sales each day.

Weaver said he was known as “The Meat Man” or “Jewelry Man” depending on the area in which he lived.

The 65-year-old Weaver has written a book about his double life, where on the one hand he made a lot of money and “danced” with society’s elite, and on the other he ran with a “junkyard dog” who was a drug dealer. I am writing. And he’s an addict.

“Hell on Earth: Dancing with the Elites and Running with the Junkyard Dogs” follows his life from Altoona to California to Arizona.

In a recent interview with Miller, Weaver said he spent a short time in prison as a result of a cocaine deal in Garrett County, Maryland. He was then involved in a marijuana trade in Blair County, one of which provided him with a large quantity of percocet the night before he was arrested.

State police narcotics agents withheld charges in an attempt to get him to buy from local drug dealers.

However, not wanting to be a “snitch,” he fled the area and ended up in Oakland, California with his girlfriend, who later became his wife. He changed his name to Jeffrey Scott. They ended up in Tucson, Arizona, considered the cocaine capital of the world, Weaver noted.

The couple probably set up a jewelry business in Tucson’s new Swap Mall in the late 1980s or early 1990s.

His jewelry kiosk happened to be next to a leather store run by a young man from Nogales, a border town near Tucson.

Weaver met a young man he called Antonio. The leather goods business was at the forefront of the drug trade, supplying kilograms of cocaine each week to the Chicago and Los Angeles areas.

Weaver (or Scott) got into trouble in Tucson when he obtained the script from a clinic and used it to support an opioid addiction.

His past caught up with him. Police realized he had skipped a probation sentence in Maryland, as well as an impending indictment in Blair County.

He faces up to 17 years in prison and has decided to work with the Pima County Anti-Drug Commission.

He convinced Antonio and Antonio’s family that he knew drug dealers in Altoona who would be interested in Nogales’ cocaine.

A deal was struck, presumably with an Altoona drug dealer (actually a Pima County Narcotics Task Force officer in a Steelers hat) to sell a Mexican family 10 kilos of cocaine for $18,000 a kilo. I agree.

Once the exchange was made, a bust occurred.

Thanks to his help, Weaver’s Garrett County indictment and his pending indictment in Blair County were finally settled, his attorney confirmed.

Weaver returned to business serving customers legally in western and central Pennsylvania, but his drug addiction worsened.

He became a regular in Altoona’s “back streets” and the area he called “Little Philly.”

His business was doing well, and he was able to move out of his home in Newry into what he called his “mansion” in the Sylvan Hills development of the Frankstown Township.

As he states in his book, he slowly began to realize. It is evil, it sucks all the good out of people and turns anyone into an animal. ”

Weaver said he became addicted to heroin when he opened a store in Tyrone (I-99 Antiques) and expanded his business by moving to Duncanville.

“So in my alternate secret world, I had reached a new comfort zone in the back streets of Altoona, a hidden world where all the addicts and junkyard dogs lay,” he wrote.

His slippage became endemic, and after being robbed and shot during a drug deal in New Jersey.

He started going through bad checks to buy more heroin and moved into an unheated trailer in Bellwood with another addict.

I began to hear voices saying, “One with the earth.”

He took this to mean that everything had to be removed. He took the jewelry and dumped it in the Little Juniata River between Tyrone and Lewistown. he took off his suit.

Weaver said he and his Bellwood friends shot at a local cemetery early in the morning, which prompted him to consider suicide.

Weaver’s dad saved his life when he came to the trailer and took Weaver to a rehab center, the White Deer Run near Williamsport, “despite all the problems we had.” rice field.

“Now you’re ready for the White Deer Run. I was ready for rehab. There comes a time when you’ve gone through so much pain and misery. You lose, you lose the feeling of being left out.You have no pride.There is nothing positive,” Weaver wrote in her book.

Weaver, now in her 60s, has been clean for almost a decade. He found a new purpose in his life.

He realized, “God is the only reason I’m not dead.”

Over the years in business, he has come to know many people, including a couple he describes as “genuine Christians,” and with their encouragement he began attending the Christian Alliance Church at State College. I was.

His faith in God became perfect.

“I know for a fact, God has been with me all my life. I should have died,” said Weaver.

He remembers the first time he reached out to God. He was in the Pima County Jail and I remember him yelling, help. “

He is now on a mission to help people. He wants to open a center where people and families can come together to discuss and confront addiction openly.

He says he has helped 16 people so far.

One of them is 49-year-old DeeAnn George of Bedford County.

She, too, struggled with a dysfunctional family and began drinking and using drugs at a young age.

“I was a mess,” she said. She even considered her suicide, but when she saw Weaver’s book and she contacted him, he made a huge impact on her life.

“He spoke to me like a human being. … He builds your self-esteem,” she said, noting that he helped her get her life back.

She also started attending church and now has a job.

George said that after rehab, a person’s brain has not yet healed, but over time a person can regain self-esteem and, as Weaver discovered, “true happiness,” she said. I believe

According to George, Craig’s mission is to help others in the same way he helped her.

“He has a lot to say,” concludes George.