California lawmakers are pushing a bill aimed at protecting kids from the dangers of social media, one of many efforts nationwide to combat what U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy and other public health experts have called a youth mental health emergency.

But California's effort, like others, will likely face the same legal challenges that have thwarted previous legislative attempts to regulate social media. The tech industry has successfully argued that imposing rules governing how social media operates and how people can use online services infringes on the free speech rights of the companies and their customers.

An earlier effort to address the issue, the California Age-Appropriate Design Code Act of 2022, is currently before the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. Tech industry groups sued to block the law and won an injunction from a lower court, primarily on First Amendment grounds. The appeals court heard oral arguments in the case on Wednesday.

“At the end of the day, this unconstitutional law doesn't protect any children,” said Carl Szabo, vice president and general counsel at NetChoice, which represented the tech giants in federal appeals courts.

Like the design code law, two proposals currently before the California Assembly would overhaul the way social media users under the age of 18 interact with the services.

of First invoiceA bill introduced by state Sen. Nancy Skinner (D-Berkeley) would ban push notifications from being sent to children at night or during school hours. Skinner's bill would also require parental permission before platforms can send social media offers via algorithms designed to keep people looking at their phones.

of Second measureThe bill, introduced by Rep. Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland), would prohibit companies from collecting, using, selling or sharing data about minors without their consent or, if under 13, parental approval.

Both bills have bipartisan support and are backed by state Attorney General Rob Bonta. “We need to act now to protect our kids by strengthening data privacy protections for minors and protecting young people from social media addiction,” Bonta said earlier this year.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D), a vocal voice on young people and social media and who recently called for a statewide ban on cellphones in schools, has not publicly taken a position on the social media bill.

California's move is especially significant because, as the most populous state, it often exerts influence over other states' adoption of the standard, and it's home to some of the biggest tech companies most affected by the law, including Meta, Apple, Snap and Google parent Alphabet.

“Parents are demanding this, and that's why Democrats and Republicans are working together,” said Wicks, who, along with his Republican colleagues, is co-author of the Design Code bill, which is embroiled in litigation. “Regulation is coming, and we won't stop until we can keep our kids safe online.”

The fate of the Design Code Act is a cautionary tale: It passed with no dissenting votes and would impose strict limits on data collection from minors, mandating that children's privacy settings be set to the highest level by default.

NetChoice quickly sued to block the law, and has since won similar lawsuits in Ohio, Arkansas and Mississippi. The company is also challenging the Utah law, which was rewritten after NetChoice sued over its original version. NetChoice lawyers have also filed complaints in the U.S. Supreme Court arguing that efforts in Texas and Florida to regulate social media content are unconstitutional. Those cases have been sent back to lower courts for further consideration.

Although the details vary from state to state, the gist is the same: each law is held back by injunction and none is in effect.

“When you look at a comprehensive law like California's, it's ambitious and I applaud it,” said Nancy Costello, a clinical law professor at Michigan State University and director of the university's First Amendment Clinic, “but the larger and broader the law, the more likely it is that a court will find a First Amendment violation.”

The harmful effects of social media on children are well documented. An advisory issued by Surgeon General Mursi last year warned of a “significant risk of harm” to young people and noted that a survey of 12- to 15-year-olds found that those who spend more than three hours a day on social media are twice as likely to suffer from depression and anxiety than those who don't use it. A 2023 Gallup poll found that U.S. teenagers spend roughly five hours a day on social media.

In June, Governor Mursi called for social media platforms to post warnings similar to those for tobacco products. Later that month, Governor Newsom called for California to severely restrict smartphone use in the classroom. A bill to codify Governor Newsom's proposal is pending in the Legislature.

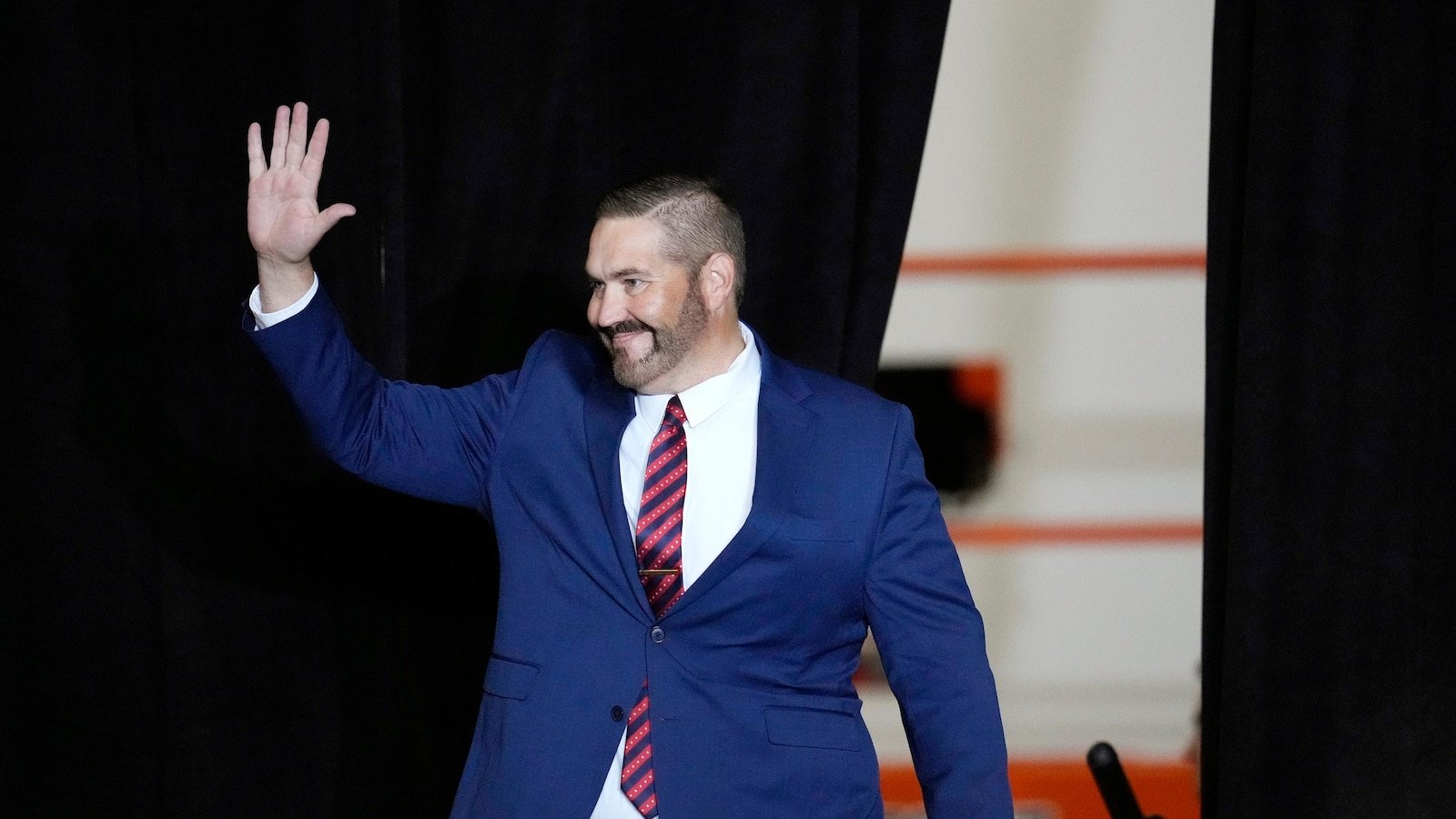

Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg apologized to attendees of a US Senate hearing in January for “the pain that your families have had to go through” as a result of social media.

(Jose Luis Magana/The Associated Press)

Federal legislation has been slow to take hold. Bipartisan Bill A bill introduced in May that would limit algorithmically derived feeds and keep children under 13 off social media was rejected by Congress. Almost nothing Despite an apology from Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg, it is impossible to meaningfully rein in tech platforms. At a U.S. Senate hearing In January, he spoke about “the kind of suffering my family had to go through” as a result of social media attacks.

It remains unclear what kind of regulation the courts will allow. NetChoice argues that many of the proposed social media regulations would violate the First Amendment by allowing the government to dictate how private companies set editorial rules. The industry also relies on federal laws that protect tech companies from liability for harmful content created by third parties.

“We hope that lawmakers will understand that they can't circumvent the Constitution, no matter how much they want to,” said Szabo, the NetChoice attorney. “The government is not a substitute for parents.”

Skinner tried unsuccessfully last year to pass a bill to hold tech companies accountable for targeting kids with harmful content. A bill passed overwhelmingly by the state Senate and pending in the state Assembly this year would ban tech companies from sending social media notifications to kids between midnight and 6 a.m. every day, and between 8 a.m. and 3 p.m. on school days. Senate Bill 976 It also calls for platforms to require parental consent for minors to use key services and to limit usage by default to 90 minutes per day, down from one hour.

“If private companies are not willing to change their products in ways that make them safer for Californians, we must demand that they do so,” Skinner said, adding that some of his proposals are standard practice in the European Union.

“Social media already accommodates users in many parts of the world, but not in the U.S.,” she says. “They could. They just choose not to.”

Meanwhile, Wicks said he believes the data bill is about consumer protection, not free speech. 1949 Congressional Bill The bill would close a loophole in California's Electronic Communications Privacy Act, preventing social media platforms from collecting or sharing information about people under the age of 18 without their consent. The state Assembly approved Wicks' bill without opposition, sending it to the state Senate for further consideration.

A more narrowly focused proposal might have a better chance of surviving a legal fight, suggested Ms. Costello, who is helping to draft model legislation led by the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health that would require third-party assessments of the risks posed by the algorithms used by social media apps.

“This means we're not restricting content, we're measuring harm,” Costello said. If harm is documented, the results would be made public and could trigger legal action by state attorneys general. Government agencies took a similar approach against tobacco companies in the 1990s, suing them for false advertising and business practices.

Szabo said NetChoice has worked with state governments to write “constitutional and common sense legislation,” pointing to bills in Virginia and Florida that would require digital education in schools. “There's a role for government,” he said. (The Florida bill was defeated.)

But with little momentum for real regulation at the national level, state lawmakers continue to try to fill the void. New York recently passed a bill similar to Skinner's, which the state senator said was a positive sign.

Will NetChoice compete for an injunction in New York? “We're having a lot of conversations about that,” Szabo said.

This story was produced by KFF Health News, a national newsroom producing in-depth journalism on health issues.