Celebrating the Erie Canal’s Bicentennial

Two hundred years have passed since the Erie Canal was completed, and New York’s governor, along with other local officials, marked this milestone with celebrations. They journeyed from Lake Erie to New York Port, stopping at various communities along the way. It was like a ten-day festival filled with parties, speeches, and public festivities, culminating in a unique “sea wedding” where water from Lake Erie was poured into New York Harbor.

The canal’s completion seemed almost destined. While support for the project was initially limited, it eventually became one of the significant endeavors for regional economic development in the U.S. Like many ambitious projects, a visionary—Jesse Holy, a flour merchant—recognized the potential for a canal. While imprisoned for debt, he envisioned a way for western farmers to tap into Atlantic ports and access new markets.

In early America, transportation posed a major challenge. Natural rivers facilitated trade, but areas lacking access to these waterways relied on poorly maintained roads. Pack animals could only carry limited loads and traveled short distances, unlike river barges that could move goods more efficiently. European engineers had successfully constructed canals to address these issues, but attempts in the U.S. were mostly confined to smaller, short-distance projects. The grand vision for the Erie Canal seemed too costly for private investments, leading supporters to seek government approval, but initial efforts failed. President Thomas Jefferson even dismissed the proposal as absurd.

Despite Jefferson’s skepticism, Holy persisted. Lacking sufficient funding, he approached the federal government for support on various infrastructure projects, including the Erie Canal. However, even with Congressional backing, President James Madison shot down the measure, deeming it unconstitutional and suggesting that such projects should be left to the states.

Holy then turned to New York Governor DeWitt Clinton, who, despite facing opposition, championed the initiative. Clinton worked to secure $7 million in bonds for the project, which soon earned the nickname “Clinton’s Ditch.” Initially, this seemed fitting, as the first 15 miles took over two years to complete amid numerous setbacks.

Nevertheless, Clinton remained committed to seeing the project through. The canal ultimately became the second longest in the world, a remarkable feat accomplished mostly by human and animal labor. Even with limited tools, Americans displayed ingenuity, developing new construction techniques as challenges arose.

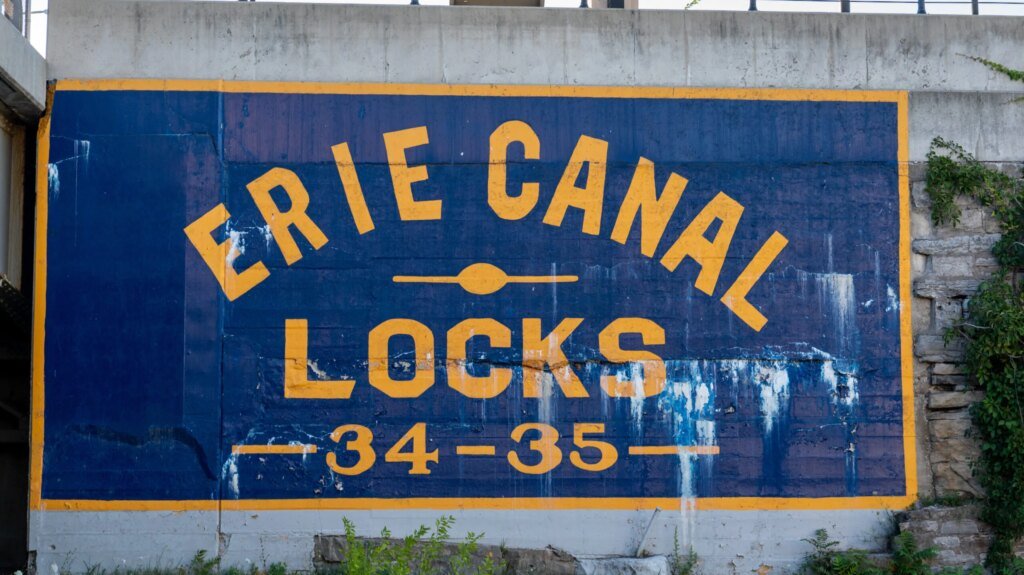

With each newly opened section, local communities began to realize the canal’s benefits. The ease of transporting goods transformed trade, and even Jefferson came to recognize the potential of Clinton’s ambitious project. After eight years of work, the canal was completed in 1825. The initial goal was to link Lake Erie with New York, but the resulting economic growth within surrounding communities surpassed expectations. New businesses flourished along the route, creating additional products for trade while also boosting tourism as visitors explored the interior.

The canal generated over $1 million in its first year, enabling early repayment of its bonds. Transport costs dropped significantly, sometimes by more than 75%. The duties collected from goods transported through the New York Port became a crucial revenue source for the federal government. Coastal residents enjoyed fresh produce, while those in the interior could access seafood.

New York City’s rise can largely be attributed to the canal, prompting other coastal cities to consider similar projects. Yet, New York had a head start and continued to thrive.

What began as a bold endeavor seen as a folly turned into a tremendous success, enhancing trade and economic growth thanks to the Erie Canal.