Howard Fisher

Capitol Media Services

PHOENIX — Tom Buschatzke says it’s not wrong to freeze new development in Buckeye, Arizona and surrounding areas due to a lack of groundwater as canary coal mines.

But the director of the State Water Resources Department said the early warning to Arizonans from the Canaries actually first occurred three years ago in Pinal County.Groundwater.

More importantly, much of the rest of this drought-stricken state is headed in that direction without new water sources, he said.

In an extensive interview with Capitol Media Services, Buschatzke said communities aren’t immune just because they’re allotted water from the Central Arizona project.

Its resources are also finite. Cities that fail to display CAP allocations also ensure that their 100-year water supply faces similar limits.

He also said developers cannot start construction today relying on the idea that treated seawater might become available sometime in the future.

Buschatke also said Gov. Katie Hobbs said in a state address Monday that he would not release an analysis of available groundwater in a location known as the Lower Hassanpasab Basin near Buckeye until Monday. He said the decision was not an effort. Don’t publish it so developers can continue building.

He confirmed that the request to delay the report was actually from her predecessor, staff member Doug Ducey. At the same time as coming up with a “potentially public solution,” he said he wanted to make it public.

When Hobbes was informed of the existence of the report, he had other ideas.

“I don’t think we can tackle this problem if we don’t know what we are facing,” she said after her speech.

Regardless, Buschatzke said the timing was legally irrelevant: Whether public or not, Buschatzke said what was in the report was a new development in the 886-square-mile area his department is investigating. He said it meant that he had not issued any permits for residential subdivisions.

But the release of the report has brought new focus to the fact that the state is facing water shortages even as people continue to move here.

“We have this dual challenge, don’t we?” said the governor. “We need to balance the need to address the housing crisis with the need to address water shortages.”

This “double challenge” is caused by a double problem.

Decades ago, lawmakers realized that the amount of groundwater available to the state stood to be driven out by demand.

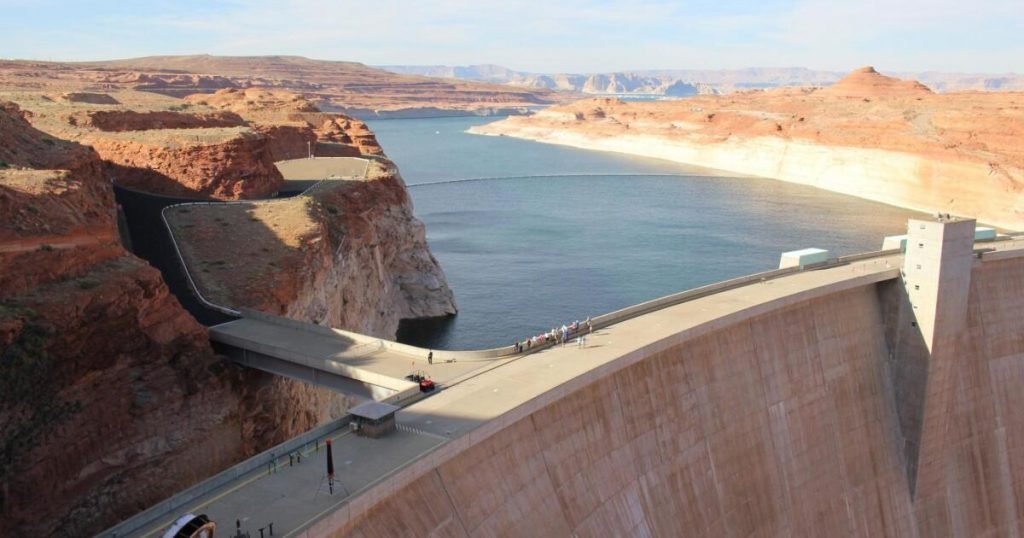

Arizona has long had the right to part of the Colorado River’s waters. But federal law was needed to authorize the construction of a Central Arizona project with the idea of reducing the need for pumps.

Then in 1980, the CAP was introduced, and legislators approved historic legislation aimed at reducing groundwater withdrawals in metropolitan areas. The idea was to achieve a “safe yield” by 2025.

The only thing is that the supply of the Colorado River, which was allotted for an unusually wet year, has not materialized recently. If you don’t agree, more reductions will be made.

But Buckeye’s report shows that as CAP water becomes increasingly scarce, groundwater is not the future solution for much of the state.

“We’ve tried to take the easy road,” Hobbes said. And the question remains whether Arizona can continue to grow at its current rate.

“I don’t know the answer to that,” she admitted.

“A lot of what we’re facing with the shortage of the Colorado River is that snowfall is being absorbed and runoff is less,” the governor continued, which she said was caused by climate change. .

“This is not something that can be solved by using less water. It’s very complicated,” Hobbs said.

But can we actually stop development?

“There are so many questions that I don’t have the answers to.” We need to keep people living and water scarcity going. “

Buschatzke said this was not surprising.

“What I have said over the years, given the fact that groundwater is a finite resource, has been allocating groundwater for various uses since the Groundwater Management Act of 1980. Yes, it was only a matter of time,” he said.

Bushzke said the Buckeye won’t be the last area to be affected.

“We don’t know exactly who is next and when it will happen,” he said.

“As always, we are in the process of improving and updating our groundwater model,” continued Buschatzke.

“And as we work on them, we may see some of this starting to see the light of day elsewhere.”

So what are your options for continued growth?

One is pumping water from the Hulkuahala Valley further west of Phoenix. A special law permits the transfer from this basin to water-scarce areas of the state.

There is also reclaimed water that has not yet been allocated, such as for cooling at the Palo Verde nuclear power plant.

In addition, the Colorado River Indian Tribe recently received federal permission to sign a long-term lease for a portion of the Colorado River waters for 719,428 acres per year. An acre-foot supports her family of three for a year on average.

But it still has its limits.

Buschatzke said the tribe is probably looking at lease terms of 25 to 30 years, too short for the community and developers to be part of the 100-year guaranteed supply.

“But you can put that CRIT water underground and divide that volume by the right math and you get 100 years. You can pull it out over 100 years,” he said. ‘

And what about desalination?

The only thing that ever happened, according to Buschatzke, was when the Water Infrastructure Finance Authority told its staff about an Israeli company, IDE Technologies, and a plant that could supply Arizona with water in the future. I instructed them to discuss the possibility of supplying water to the state. But that is far from certain, he said.

“At this time, it is not possible to offer potentially desalinated water as an endorsement of someone’s guaranteed water supply program.

“There are no plants installed, no plants under construction. We are not producing water. We have to produce water,” he said.

And it actually says nothing about being available for 100 years.

“Disposal could be part of the solution,” Buschatzke said.