This is what it takes to make small cities safe.

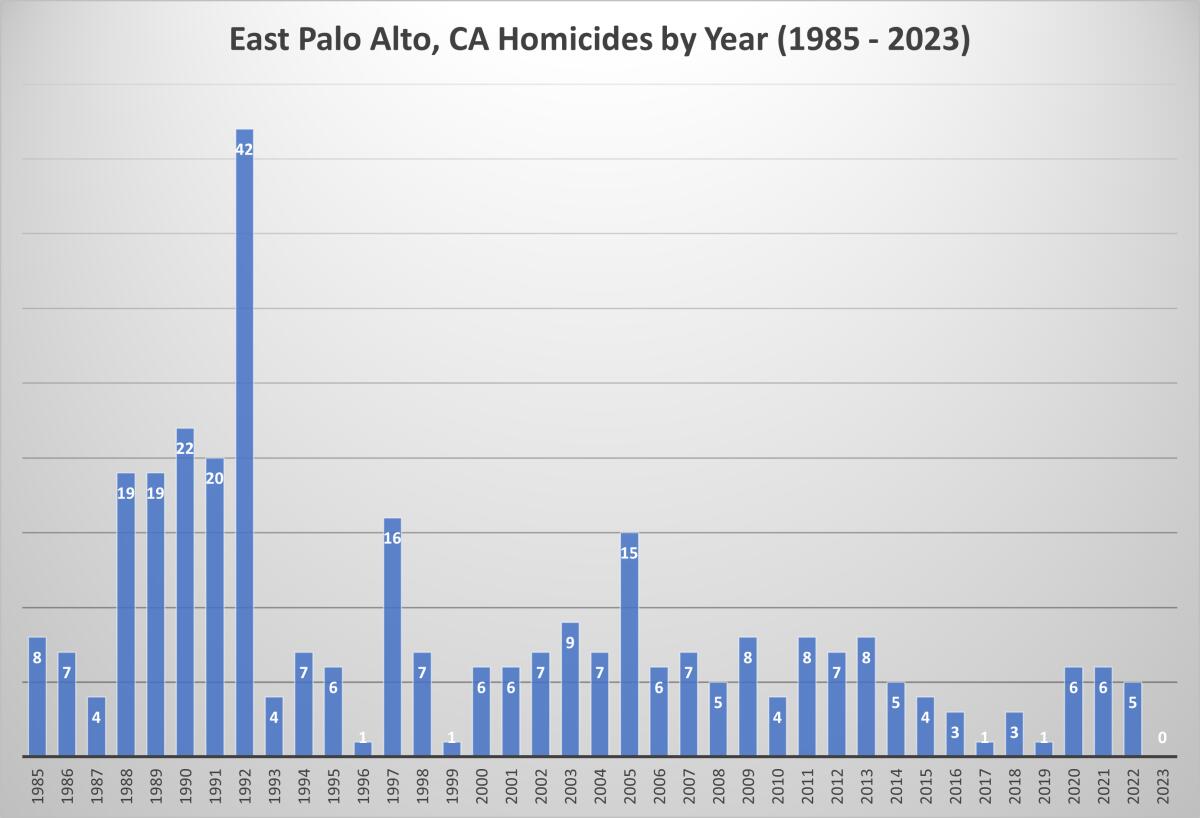

In 1992, East Palo Alto was dubbed the “Murder Capital” of the United States, with 42 murders occurring within its 2.5 square miles. This was the highest homicide rate per capita of any other city of its size. According to East Palo Alto Police Department statistics released last week, a complete turnaround appears to have occurred in 2023, with no homicides.

Law enforcement leaders, residents and city officials say a complex combination of circumstances has turned a crime-ridden area into what the mayor now calls “one of the safest places to live on the Peninsula.” are doing.

The San Francisco Peninsula that Mayor Antonio López mentioned is home to Stanford University, the wealthy towns of Atherton and wealthy Palo Alto. Even though median household income has increased dramatically and the typical home price is just over $900,000, residents and city leaders continue to struggle with the simple notion that gentrification has solved the city's problems. It makes fun of ideas that are too much.

They argue that poverty and crime are not necessarily closely related. They point out that development has increased since it earned the dreaded title of Murder Capital, including IKEA and the Four Seasons Hotel. It also allows for more employment opportunities, youth programs, and community policing. And time.

“Despite our past mistakes, we can move forward and set an example for everyone,” Lopez said.

::

East Palo Alto, wedged between San Francisco Bay and Palo Alto, was home to just over 28,000 people at the last census. Median household income is $103,000.

as high tech companies As the surrounding area prospered, the city experienced significant gentrification. Rising home prices have left some low-income residents of East Palo Altan feeling forced out.

East Palo Alto, now a predominantly Latino neighborhood, was once a landing spot for black families facing redlining by lenders and real estate agents.

This is where Paul Baynes' family landed in 1962, at a time when the city was predominantly black.

“East Palo Alto was considered a little black mecca,” said Baines, who still lives and works there.

Many people of color owned homes and looked out for each other. Baines, the pastor of St. Samuel's Church, refers to that time as “B.C.,” or before the cracks.

At the time of the nation's crack cocaine epidemic, about 17 percent of East Palo Alto residents lived in poverty, higher than the national level.

“When the rift started, it just depressed the family,” Baines said.

East Palo Alto was also enduring growing pains. After years of neglect by San Mateo County government, the community voted to incorporate as a city in 1983.

Paul Norris went to work for the newly created East Palo Alto Police Department shortly after, in 1987, when there was “drug sales on almost every street.” There were only four murders that year, but in the following years that number increased dramatically, reaching double digits.

Most of the murders involve drug traffickers or gang members fighting over territory, Norris said.

Norris, now the department's acting sergeant, recalled working the night shift when there were six shootings in the city. He waited with the body for 45 minutes until paramedics arrived.

“It looked like a war zone,” he said.

Clyde Burgess was on the front lines. Raised in East Palo Alto, he went to college but returned in the late 1980s with drug problems. He said the drugs were so plentiful that they were littered on the streets, with scraps of sales to patrons driving into the chaotic city to buy.

“Cover your matches and scrape up anything that falls off the ground,” he said.

The sound of gunfire was the soundtrack of the city. Residents often said Palo Alto had a drive-in. There was a drive-by in East Palo Alto.

One New Year's Eve, Vilges recalled putting a flower pot over his head to protect himself as he went to buy crack cocaine.

Vilges was caught up in a crackdown in the 1990s and was arrested after selling controlled drugs to an undercover informant who was caught on video. He called it a blessing.

He spent nearly a year in a treatment facility before attending school to become a licensed drug and alcohol counselor. Now 70, he works with the homeless as a case manager at WeHope, a nonprofit organization in East Palo Alto.

::

In 1992, East Palo Alto gained national notoriety.

At the time, the city was home to 24,000 people and had the highest homicide rate in the United States, with the number of homicides jumping from 20 the previous year to 42.

In 2000, the body of a gunshot victim lies in an alley off Fordham Street in East Palo Alto, just behind gang graffiti.

(Carlos Avila Gonzalez/San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

This amounted to 175 murders per 100,000 inhabitants.

“This case received tremendous attention here in California,” said Police Chief Burnham Matthews at the time. “It was a city that really needed help.”

Assistance came in the form of external law enforcement agencies. Palo Alto donated four police officers. Menlo Park gave him two. The San Mateo County Sheriff's Department has since hired 18 deputies, and the state has assigned 12 highway patrol officers. The department's power has more than doubled with the introduction of outside directors.

By 1993, the number of murders had fallen to four, according to police statistics.

Sharifa Wilson, who was mayor in 1992, welcomed the police support at the time, but stressed it was “not the answer”.

“Part of the problem… was the lack of economic opportunity,” the 73-year-old said. “We didn't have access to capital to establish ourselves.”

Because of the attention given to East Palo Alto, she said, the city was able to get help from the state and move forward with shopping center development by implementing policies that require all businesses to hire from the community.

“We're not raising our kids to be drug dealers,” she says. “Creating opportunities for them to work made a difference.”

Wilson, who still lives in the city, said crime has decreased because of the community. At one point, residents formed a group called “Just Us” and were going to street corners and taking pictures of the license plates of people driving up to buy drugs. From there, police sent a letter to the registered owner informing them that their car had been seen in a drug-heavy, high-crime area. (Wilson said one of the letters was addressed to a judge whose car his son used to buy drugs.)

Local nonprofits and faith-based organizations focus on engaging youth in after-school programs and activities that keep them away from crime.

“This is really a testament to the community's commitment to solving their own problems,” Wilson said. “East Palo Alto has always been a resilient community. The people there really care and care about the community they live in.

“The fact that we were labeled the murder capital gave us the attention we needed. And we took that attention and turned it into something positive. “I changed it,” she added. “Give me a lemon and I'll make you lemonade.”

::

East Palo Alto, once the “murder capital” of the United States, had zero homicides in 2023.

(East Palo Alto Police Department)

East Palo Alto's homicide rate has remained in the single digits for 17 years. One murder occurred in the city in 2017 and 2019.

Shortly after midnight on New Year's Day this year, Police Chief Jeff Liu texted city officials with the long-awaited news. The number of murders in East Palo Alto has finally dropped to zero.

“We always had at least one, but to get to zero is just a monumental accomplishment for the entire community,” Liu said. “It's always like a goal that slips through our fingers.”

In addition to police work, Liu praised residents and the efforts they put into reducing crime through supporting youth and alerting officers to what is happening in the city. That wouldn't have been possible if the department hadn't built trust, he said.

When Lopez heard the news, she said, “I almost cried.” The mayor cited the city's investment in police funding to bring police salaries on par with other law enforcement agencies.

“What I love about East Palo Alto is that this area is a model not only for the peninsula, but also for the country on how effective community policing can be,” he said.

With homicides down to zero, leaders are optimistic about the future.

Baines, a pastor and co-founder and president of Wehope, said he is “proud of our city.”

“There are a lot of people out there who stand on the shoulders of our heroes who have stayed in this community and lived through the best of times before, gone through the worst of times, and now come back to the good times,” he said. . “Currently, we have zero murders, and we want to keep the murders at zero.”