California's crime rate began a historic plunge in the early 1990s and has been falling ever since, with some small increases, including during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it took more than a decade for the law to reflect this trend.

Lawmakers continued to pass tough laws against terrorism crimes until 2011. The wrong mindset of the people Crime there was higher than in recent years. As federal courts threatened to order indiscriminate releases from the state's unconstitutionally bloated and cruel prison system, California launched a decade of criminal justice reform, with lawmakers and voters rolling back some of the horrific and excessive punishments adopted over the past half century.

Now the debate over crime and punishment has shifted direction again, with Republican politicians generally wanting to end the era of reform and return to tougher penalties, while Democrats are split between continuing reform and cutting back.

This is the background to the heated debate over the state. Senate Bill 94, Value Proposition Sen. Dave Cortese (D-San Jose) has introduced a bill that would reconsider the sentences of hundreds of California's elderly inmates who were sentenced to life before June 5, 1990, before the reforms were put into place.

Life imprisonment did not exist in California until 1978, and was rarely used for more than a decade after that, but became the norm after voter attempts in the 1990s made life imprisonment mandatory for some crimes.

More recently, reform laws have returned some sentencing discretion to judges.

SB 94 follows the sensible path of recent legislation and U.S. Supreme Court decisions that allow parole hearings for most people sentenced to life in prison for crimes committed as minors.

However, this system has been controversial because it applies to people who commit crimes as adults, and unlike young people, they cannot be blamed for their criminal acts on their immature brains or lack of adult judgment. However, it is worth noting that most of the criminals subject to this system commit their crimes in their late teens or early twenties.

The law does not directly resentence or release inmates, but instead creates a multi-step process for inmates to appeal for resentencing, but only after they have spent at least 25 years in prison. It does not apply to serial killers, cop killers, or sex offenders.

In other cases, judges have complete discretion to hear and deny parole requests. If a parole hearing is granted and the Board of Parole Hearings determines that the defendant is suitable for parole (because the defendant has presented sufficient evidence of remorse and rehabilitation after decades in prison), the governor can still deny release.

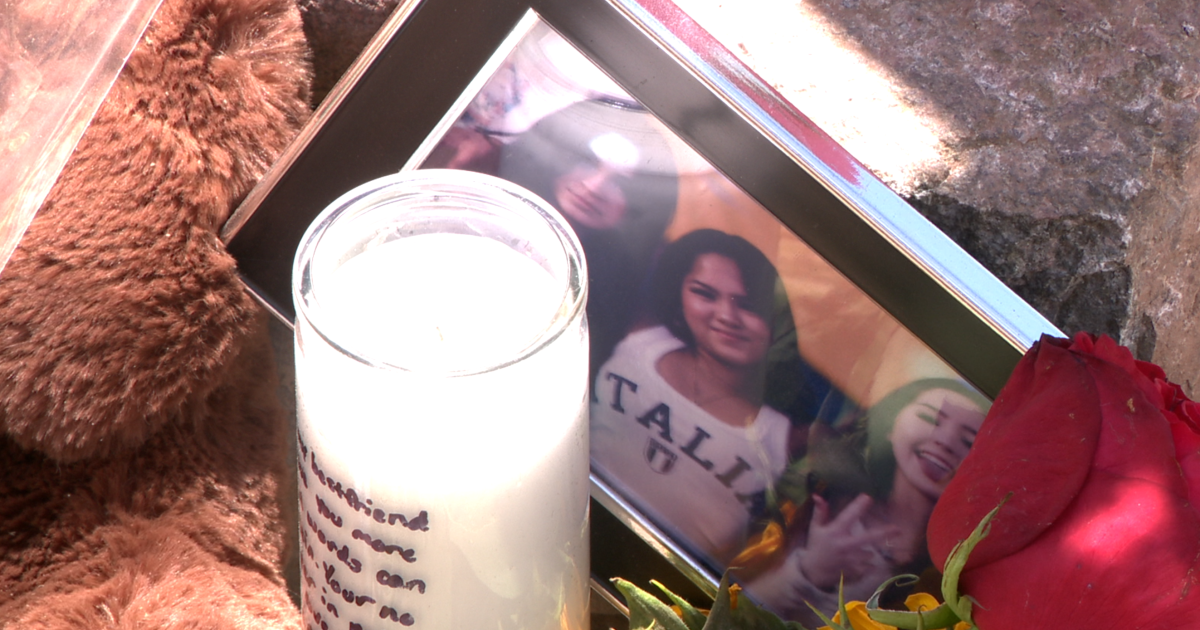

Most of the offenders whose cases are appealed are now in their 60s or 70s, well past the peak of their violent crime years, and for many, more than half a century has passed before they are eligible for appeal.

The basis of this bill is not pity, but pragmatism and a careful sense of justice. Few Californians probably have any sympathy for a murderer who spends decades in prison. But there is less and less value in keeping people in prison for heinous crimes they committed long ago, when they were young and foolish.

There are ongoing costs to housing, feeding, clothing, and medical care for seniors in prison, and it is worthwhile for society to limit sentences to a few decades for even the most brutal offenses after ample evidence has been presented that parole poses little risk to society.

And yet in our system, even the most rational sentencing reforms take a backseat to partisan politics. With Republicans and Democrats vying for control of Congress, the fight over criminal justice measures is being fought with an eye on a handful of contested House districts, and both sides are using fear of crime to get voters to the polls.

It's part of the fight over whether to repeal Proposition 47, which reverted certain theft and drug offenses that could be charged as felonies in a tough-on-crime era back to misdemeanors. It's also part of the issue at stake in SB 94.

If the bill doesn't pass the House by Saturday, it will be voted down. It would be a shame to see such a safe, cost-saving reform killed in partisan disputes.