By the time 38-year-old Caryl Chessman was executed on the morning of May 2, 1960, he had been on California's death row for 12 years. His dark, rough features were recognized around the world, and his name became a rallying cry from South America to the Vatican.

He was mid-century America's toughest hooligan intellectual, a self-taught high school dropout who wrote and published four books while awaiting death. Although he ostentatiously boasted about his vast criminal activities, he swore he was innocent of the charges that made him infamous.

He sparked literary acclaim, hunger strikes, protest songs, a diplomatic crisis, and a crisis of conscience among Catholic governors.

He is almost forgotten today. But Chesman's case dominated the death penalty debate for years. His case was unusual because apart from his talent as a writer, his public relations power, and his length of stay on death row (a record at the time), he was never convicted or even charged with murder. .

In this series, Christopher Goffard revisits old crimes in and around Los Angeles, from the famous to the forgotten, the momentous to the obscure, and digs into the archives and memories of those who lived there.

However, he became infamous as the Terror of Lover's Lane. Spanning four days in late January 1948, the Red Light Robbery (so called because his late model Ford was equipped with police-style flashing lights to deceive his victims) robbed Malibu and Laurel. They robbed a couple at gunpoint in the foothills of a canyon. A remote road above LA and Pasadena.

In one attack, the gunman forced a woman to accompany him to his car (prosecutors say polio made it difficult for her to stay 20 feet away) and forced her to perform oral sex on him. Two nights later, the gunman kidnapped the 17-year-old girl, drove her around the city for hours, and again demanded oral sex. The two cases will be prosecuted under the state's Little Lindbergh Act, which carries the death penalty for kidnapping with bodily injury.

After a high-speed chase, police arrested Chessman at 6th Street and Vermont Avenue in a stolen Ford connected to a stabbing in Redondo Beach. During interrogation, Chessman claimed to have implicated himself in the crime of robbery, but claimed that police broke his confession.

Unfortunately for Chessman, whose arrogance and thirst for attention were among his most distinguishing characteristics, he insisted on acting as his own lawyer. He cross-examined sexual assault victims, who identified him as their perpetrator. The teenage girl looked straight at him and said, “I know it's you.”

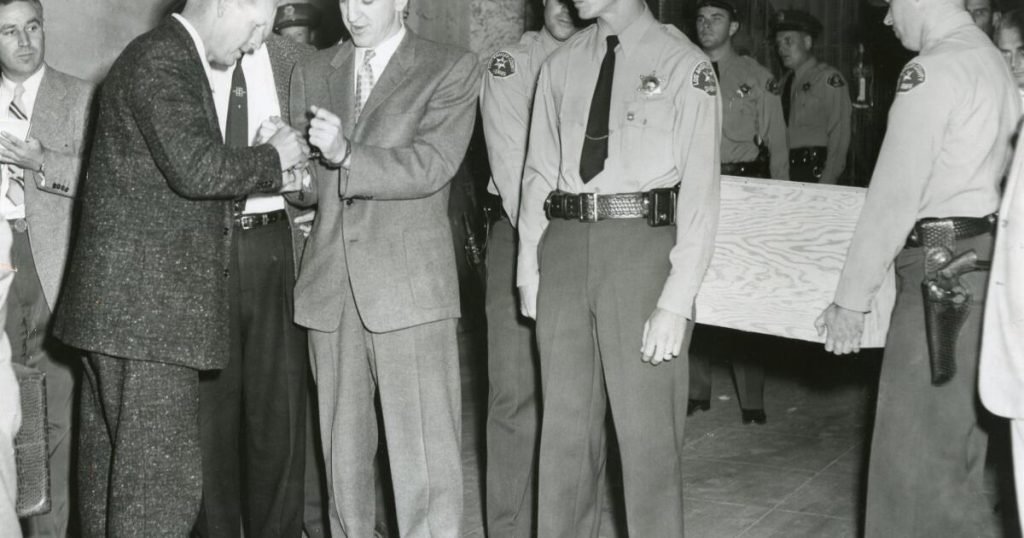

Caryl Chesman, 1958, 10th anniversary of arrest. By that time he had become a best-selling author.

(Los Angeles Times)

“He liked to boast that he was a great criminal, but great criminals don't always get caught,” Theodore Hamm, who wrote a book about Chessman, said in a recent interview. told the Times. “He thought he was the smartest guy in the room and could outwit any prosecutor and convince the jury. That obviously didn't work in his favor.”

Jurors found him guilty of 17 charges in a month-long crime spree. He was 26 years old and wearing a defiant grin when the judge handed down two death sentences. His 12-year legal battle to avoid the San Quentin gas chambers (what he called “those ugly waiting rooms”) attracted worldwide attention, as did his prison writings.

His 1954 memoir, Death Row Inmate 2455: His Own Story, became a bestseller.

He describes his face, with its battered nose and large features, as “a youthful face scarred by violence that has seen too much, as if it had found its rightful place in a gallery of doomed people.'' “A predatory face.”

Born in Michigan and raised as a devout Baptist in Glendale, he became aware of the “shame and degradation” of poverty when his father's business failed.

He wrote of a childhood in which he learned to despise society and its norms, concluding that “whatever can be wisely escaped, has been escaped.” He spent years in juvenile halls, juvenile halls, and prisons.

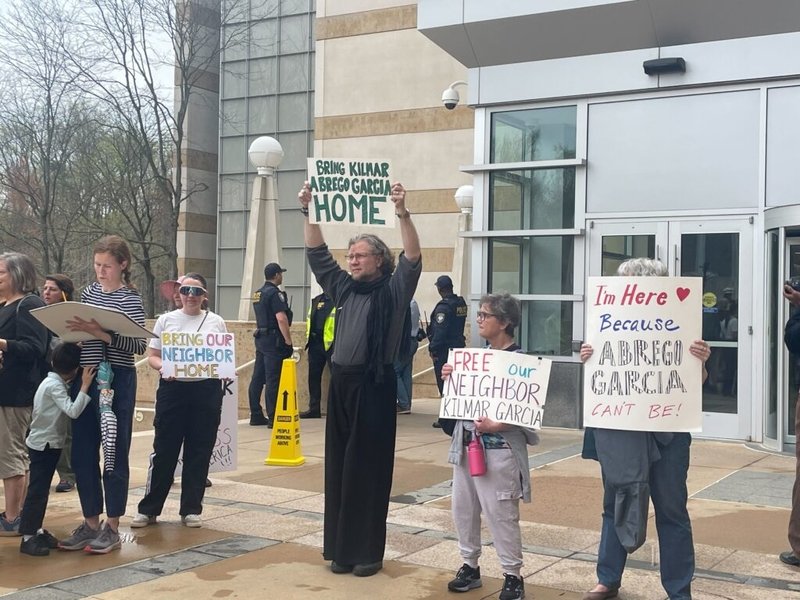

Caryl Chessman's case has sparked petitions and protests from Los Angeles to South America. At the time, his 12-year sentence on California's death row was the longest on record.

(Ray Graham/Los Angeles Times)

He said he loved the game of “cops and robbers” and became an expert at prevaricators. Arrested on suspicion of theft on his 17th birthday, he told police “one big lie after another”, using “a foolproof method of telling near-truths, half-truths, but never the whole truth”. ” was developed.

He described himself as “a grinning, brooding young criminal psychopath, defiantly and willingly bound by the psychopaths.” He set up brothels, liquor stores, and gas stations “using hate and intrigue as tools of his trade.” During a shootout with police, he yelled, “Come on, you dirty bastard, let's play!”

His long criminal history was indisputable, but it's easy to suspect that he glossed over some of his outlaw exploits. His stories had a sense of self-dramatization. He understood that people who want attention get involved in crime, and society's weakness for outlaw heroes.

“Be a violent, robbing, murderous bastard, and your reputation will be guaranteed,” he wrote. “One of the peculiarities of the Square is its strange tendency to glorify scoundrels and villains.”

In some circles, his writings on death row were greeted with enthusiasm. According to the New York Times, it was a “brilliant contribution” to criminology and, as Partisan Review put it, evidence of “self-salvation.”

“He impressed New York intellectuals,” Hamm said. In a post-war era filled with optimism about the possibilities of reform, “he came to represent the reformed prisoner. Evidence of his rehabilitation was woven into pop psychology about reform.” That was his clear explanation.”

Eleanor Roosevelt, Ray Bradbury, and Aldous Huxley signed a petition exonerating Chessman. Petitions flooded Governor Edmund “Pat” Brown's office. He was a Democrat who believed Chessman was guilty but objected to the death penalty for religious reasons. In 1959, he denied Chessman's leniency, stating that Chessman showed no repentance, but rather “steadfast arrogance and contempt for society and its laws.”

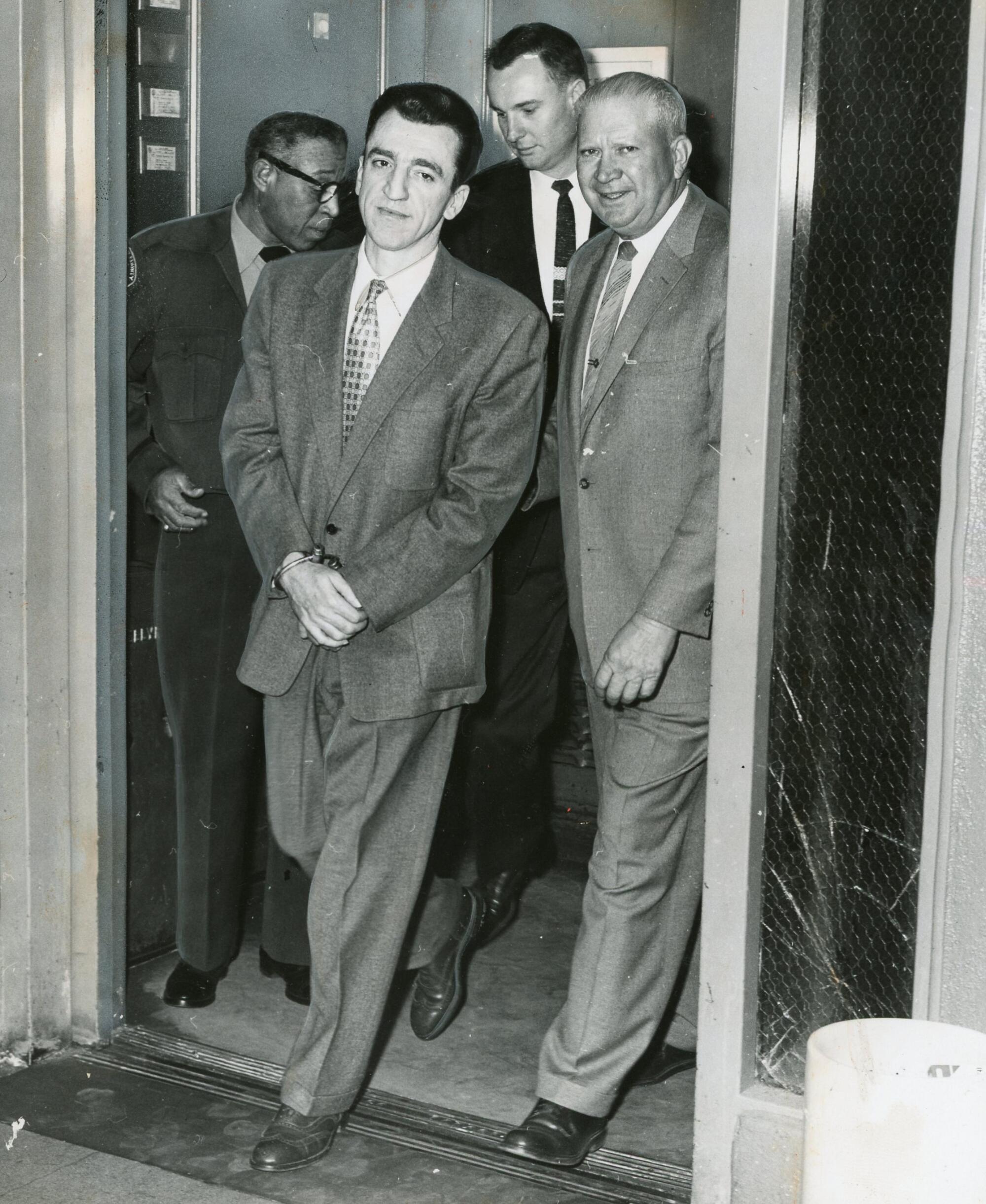

Caryl Chessman, who was being escorted to San Quentin's death row, asserted her defense at trial.

(Los Angeles Times)

Chessman appeared on the cover of Time, and editorials supported him around the world, from the Vatican newspaper to London's Daily Mail.

Ronnie Hawkins recorded a protest song, “The Ballad of Caryl Chessman,” whose lyrics captured the emotions of many sympathizers. What they say may be true, but what good would it do to kill him? Let him live, let him live, let him live. I'm not saying forget or forgive… If he committed a crime, put him in jail for a long time, but let him live, let him live, let him live…

The Los Angeles Times was not sympathetic. The editorial denounced the “madness of rescuing Chessman” and argued that the real outrage was that his execution was delayed by prolonged legal gamesmanship and political cowardice.

“Grinning, arrogant, quick-witted and alive – the chessman who committed unspeakable crimes is a great reproach to the conscience of the nation,” the Times claimed, and his supporters called him He said that he was ignorant of the seriousness of the crime, saying, “The newspapers didn't dare to report it.'' Reveal the gruesome details. ”

In her memoirs, Caryl Chessman described herself as having a “predatory look that seemed to have found its rightful place in the gallery of soulmates.”

(Edward Gamer/Los Angeles Times)

The U.S. State Department warned Brown that Chessman's execution could incite protesters during President Eisenhower's scheduled visit to Uruguay. Chessman was a celebrity in the cause. Brown recently received a phone call from his 21-year-old son, Jerry, a seminarian and future governor, pleading with his father to spare Chessman's life.

The governor ordered a moratorium on the death penalty, but when he asked lawmakers to suspend the death penalty, they refused. Anti-Chessmen crowds burned effigies of Brown and booed him and his family in public.

Prison officials tried to muzzle Chessman, but Chessman continued writing and the pages were smuggled out. Eight times he was assigned a date with the dressing room, and eight times he won by delay.

In the end, Brown argued that he was powerless to stop the execution because the state Supreme Court had ruled against Chessman.

Chessman denied to his death that he was a red light bandit. He suggested that he knew who the “real” Bandit was, but refused to say so. One of his final comments was, “I hope my fate has made some contribution towards the abolition of the death penalty.”

The circumstances of his execution gave further impetus to critics who considered the system capricious and absurd. That day, Chessman's lawyer persuaded the judge to grant him a brief reprieve, but the judge's secretary made the mistake of calling the prison to break the news, and by the time the call got through, Chessman was dead. .

Chessman wanted his ashes to be interred with those of his parents, but Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale refused because Chessman was “unrepentant.”

The case galvanized opponents of the death penalty, and reformers used it to call for changes to kidnapping laws. California executed another inmate under the Little Lindbergh Act in 1961, the last non-lethal crime, and the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the death penalty 11 years later (although the death penalty revived). In 2019, Governor Gavin Newsom declared a moratorium on executions in California.

The incident plagued Brown's political career. Brown knew his role in opposing the death penalty would be no small feat when Ronald Reagan defeated him as governor. Although Brown believed Chessman to be a mean and arrogant man, not doing more to save Chessman would be a source of deep regret.

There was political expediency “for elected officials who had programs they wanted to implement in the public interest,” Brown said decades later. “I firmly believe in all of that, and I think they should have found a way to save Chessman's life.”