Understanding US-Soviet Relations and the Containment Policy

Looking back, US relations with the Soviet Union were primarily defined by the containment strategy. The concept was straightforward: communism, along with the Soviet Union itself, posed a significant threat to global stability. While it was possible to challenge communism on an intellectual level, things took a different turn when the Soviet Union began actively imposing its brand of communism on neighboring countries. Essentially, something had to be done to prevent its spread.

After World War II, the United States faced a couple of choices. They could confront the Soviet Union directly, maybe risking another worldwide conflict, or they could limit the reach of communism to Soviet influence and wait for the system to collapse under its own weight. It was, I think, a tough call either way.

Another strand of the containment policy involved supporting rebels, both within the Soviet Union and in its satellite nations. The United States even went so far as to recruit and train local insurgents, often taking Indigenous people and preparing them to return home as nationalist leaders, ready to rise against Soviet-aligned governments.

For nearly a decade post-World War II, the CIA and the State Department spent substantial funds to implement these containment policies. Unfortunately, many heart-wrenching tales emerged—stories of dedicated freedom fighters pulled from refugee camps, only to return home, ignite uprisings, and then get captured and executed by Soviet forces.

Despite these setbacks, the recruitment and training efforts persisted, based on a belief that eventually the right combination of personnel, resources, and local sentiment would lead to revolutionary success. But honestly, little seemed to materialize in the way of tangible results.

Even amid the era of Soviet propaganda, the US struggled to showcase any significant outcomes for its investments beyond a temporary lift in morale. Yet, there were flickers of opposition and hints of progress all over. Take, for instance, 1953 when East German workers staged a strike, only to have their efforts quelled, with its leader thrown in prison. Other countries experienced similar fleeting moments of dissent, but ultimately, those in power, often trained by Stalin himself, crushed any resistance.

The US attempted to bolster these efforts, supplying support through Radio Free Europe. Still, meaningful change in governance remained elusive. While the Soviets aimed to export their revolution, there were no significant shifts from Soviet control towards freedom.

Then there was the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, which offered a glimmer of hope for US policymakers. Local leaders, motivated by Stalin’s death and a loosening of oppression, sought to break free from Soviet control. The CIA and State Department sensed a potential coup brewing!

However, despite the excitement and encouragement from Radio Free Europe, when the Hungarians rose up against their oppressors, the US hesitated. Even amidst a shaken Politburo, the US remained passive, ignoring cries for assistance, and as a result, the revolt was brutally suppressed by Soviet forces. The leaders faced execution, and once again, Soviet power tightened its grip.

Still, the containment strategy persisted. Although many leaders were disillusioned by the failed Hungarian revolt, the idea of inciting rebellion within the Soviet bloc continued to be pursued.

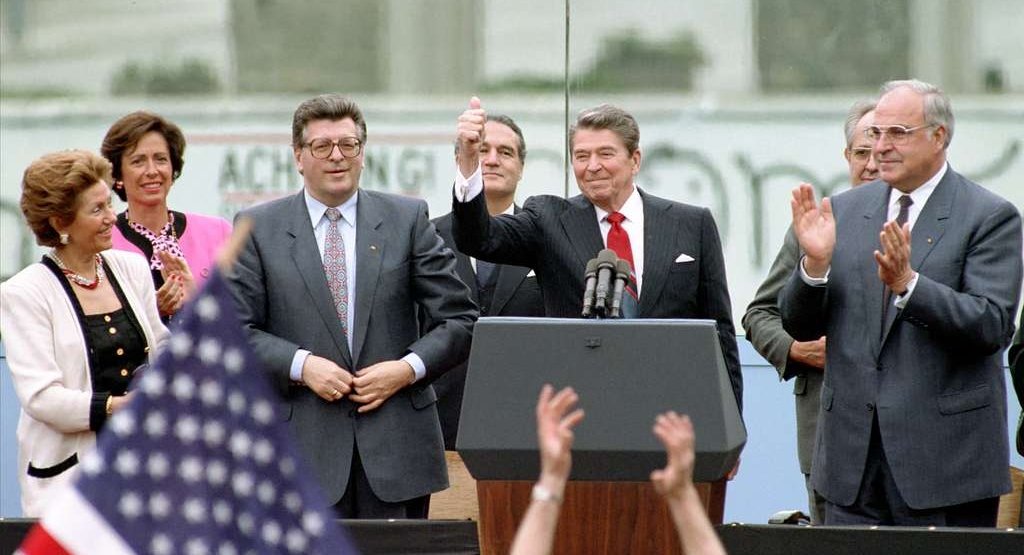

Most of these attempts fell flat until Ronald Reagan confronted the Soviet Union directly, leading to a military standoff that would eventually contribute to the collapse of their system. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union were pivotal moments; it became clear that, while the Cold War might be over, Russia never fully reintegrated into the global community.

With minimal experience in democratic practices, free speech, and individual rights, Russia clung to its authoritarian traditions. It’s as if, in some way, World War II never truly ended for them.

Contrastingly, unlike Germany and Japan, Russia seemed to resist a system that prioritizes people’s rights and government accountability. They turned down opportunities to participate in the Marshall Plan and economic rebuilding efforts, opting instead to export revolution and violence as a way to assert their global stance.

Discussions surrounding the containment policy continue, but it seems unlikely that it will shift until Russia acknowledges its role on the world stage. Until that day comes, the United States’ foreign policy will likely remain focused on countering Russia’s ambitions. Unlike Russia, the US has no desires for territorial expansion; rather, its goal is a stable world order grounded in the rule of law, supporting political freedoms, individual rights, and economic liberalism.

Ultimately, until Russia decides to abandon its expansive goals and move away from being a global outcast, US foreign policy should involve confronting Russia’s actions in Ukraine, pursuing genuine coexistence, combating terrorism and injustice, and building relationships compatible with the 21st-century global order.