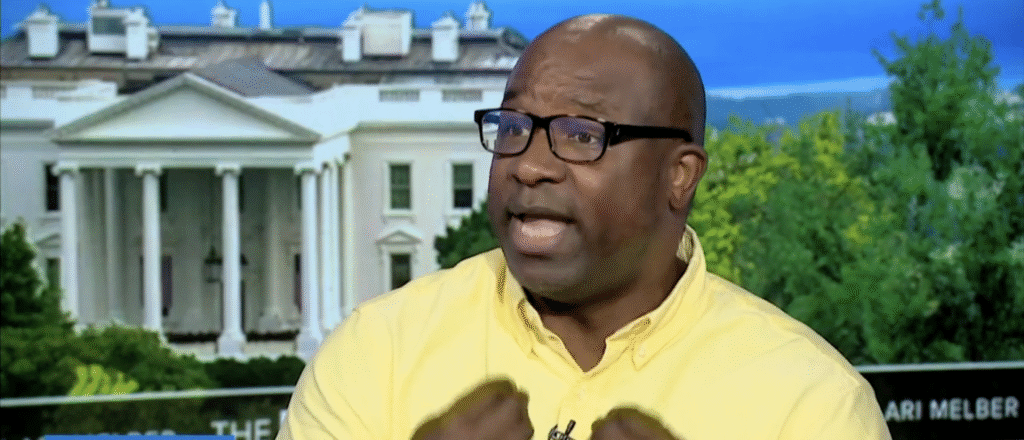

Jamal Bowman, a former congressman from New York, who previously faced controversy for pulling a fire alarm during a critical voting session, has made a return to the public eye. After entering a guilty plea to a misdemeanor and paying a fine, he’s now speaking out again.

During a recent appearance on MSNBC, Bowman suggested that serious health issues prevalent in the Black community—like heart disease, cancer, obesity, and diabetes—can be attributed to the daily stress of dealing with racial slurs. He mentioned, “The stress that we have to deal with being called N-words either directly or indirectly every day” as a contributing factor.

It’s been a challenging time for the Black community. Recently, Whoopi Goldberg made an eyebrow-raising comment on ABC’s The View, implying that Black Americans might fare better living in Iran. She expressed concern about violence over differences, stating, “That’s not good.” This prompted co-host Alyssa Farah Griffin to question Goldberg’s perspective, emphasizing that living in the U.S. today is vastly different from living in Iran.

Goldberg responded simply with, “If you’re Black,” which raised eyebrows. Some find her viewpoint surprising, especially given Iran’s reputation as one of the most oppressive countries, as indicated by the Human Freedom Index from the Cato Institute and Fraser Institute.

Bowman’s comments raise further questions. How does the daily stress of hearing racial slurs relate to an increase in diseases in the Black community? I mean, when was the last time someone directly said that word to him? How do those indirect experiences even work? It’s almost like asking whether secondhand smoke leads to health issues—could hearing slurs from a distance have a similar impact? Is it something encountered at work, church, or maybe even at a grocery store?

On the topic of diabetes, the National Institutes of Health has reported that numerous biological factors significantly contribute to the disease’s prevalence among Black Americans. They found that various health metrics like body mass index and blood pressure levels play a key role.

Some studies point to obesity as a critical issue, often linked to what’s described as “systematic racism,” particularly affecting Black women. Yet, Thomas Sowell argued years ago that the narrative around low-income people being unable to afford nutritious foods has shaped their eating habits—a connection that seems underexplored in mainstream discussions.

Is systemic racism really that limiting? If it is, why has obesity seemingly worsened despite societal changes? And then there’s cancer—Cleveland Clinic describes it as often genetic, influenced by changes in cell activity. The National Cancer Institute mentions chronic stress as a potential health risk, but the link to cancer remains uncertain.

It’s perplexing how Dr. Bowman frames these health issues, emphasizing a narrative of systemic oppression. But nuances in these discussions often get overlooked.