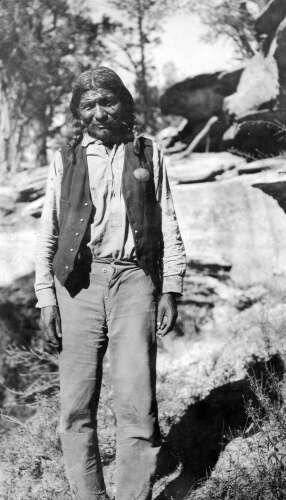

Emerging in 1921, the Posey became rebels and rebels as settler cattle and sheep continued to encroach on traditional Ute and Paiute lands and hunting grounds. Posey died two years later, either from a gunshot wound or from flour intentionally poisoned with strychnine. He is buried somewhere in Bears Ears National Monument. (Photo courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society)

By the 1920s, most of the western United States was settled. There were Ford cars, phones, retail stores, and small-town newspapers. But there was also injustice, racism, and armed white groups. His one of the last Native American conflicts occurred a century ago this month in Blanding, Utah.

It then flowed into what is now Bears Ears National Monument. Called the Posey War, two Paiutes died and a Ute family was imprisoned in a World War I-style barbed wire fence.

By the spring of 1923, 55-year-old William Posey had become an established rebel behind many cattle thefts, but also a leader.

Historian Robert McPherson said, “Legitimately or not, his growing reputation suggests that he was in the limelight and that he was behind the growing resistance.

Two young men stole a calf and ate it. Dutchies Boy and Joe Bishop’s Boy admitted the theft to an old Ute named Polk who was once an agitator himself. Despite my parents’ assurances that I would obey the law, I went into hiding and went into hiding.

They were boys, not 18 years old. At trial, the boys found him not guilty within three hours, but months later, more thefts followed. Joe Bishop’s Boy and another young man, Sanup’s Boy, raid sheep camps and take what they want.

“The New Year of 1923 started off without incident,” said McPherson. “But, like previous outbreaks of violence, small acts suddenly turned into big events. History doesn’t repeat itself, but the patterns of history do.”

The two men, now old enough to be adults, surrendered to stand trial for branding. Armed guards prowling around the young men interrupted the boy’s father. This time, the jury found two of his youths guilty, but between verdicts and sentences, their acquiescence turned to resistance.

Joe Bishop’s Little Boy beats Sheriff William Oliver with a stick. The sheriff attempted to shoot the defendant, but his pistol misfired twice on him. The assailant moved quickly, grabbed the sheriff’s gun, jumped on his horse, shot the sheriff with his own pistol, wounded the sheriff’s horse, and fled town. Sunup’s Boy rode hard into the Ute community of Westwater, south of Posey and Blanding.

In response, and against precedent, the locals armed themselves and began rounding up all Ute Indians, regardless of whether they had a role in theft, trial, or escape. Joe Bishop’s father, one of his convicted youths, vowed to find his son and return him for justice.

As Bishop drove away, Joe Black, a local white resident, caught up with him and said: If you don’t turn around and turn back, I’ll show you my guts here.”

“This news quickly spread through branding, and everyone stopped what they were doing, ran for horses and guns, and volunteered in haste,” said John D. Rogers.

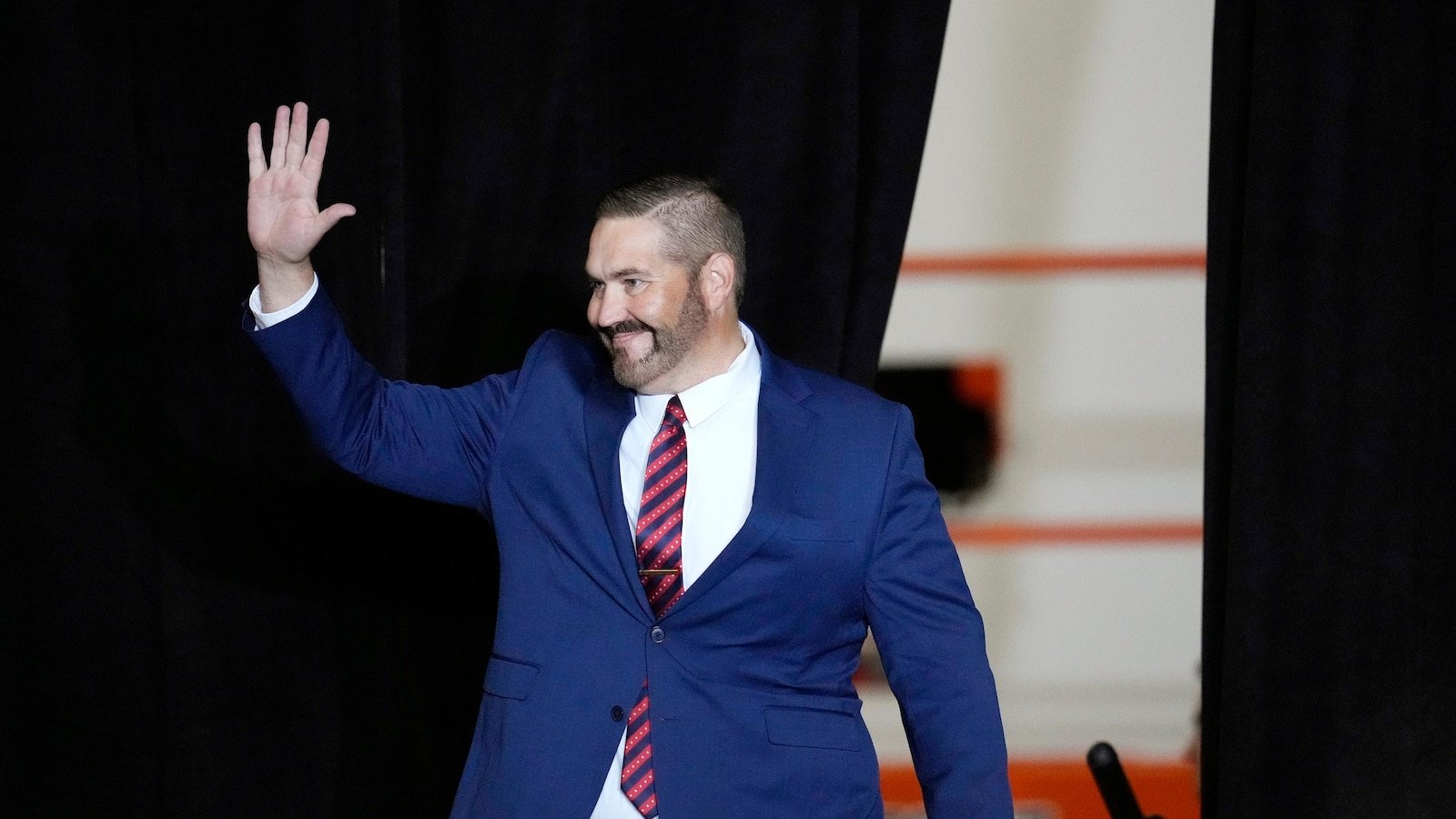

In Blanding, Utah, Ute Indians were forced into fences during the so-called Posey War of 1923. The children who had to live behind high barbed wire fences will never forget the experience. The Indian agent is the far left shadow. (Verda Washburn Collection, courtesy of the San Juan County Historical Commission)

The vengeful whites held 40 people until locals kept a 100-square-foot military palisade complete with a 10-foot-tall barbed wire fence built between a sandstone embankment and Red Mercantile. I pushed Yuuto into the basement of the school building. An innocent Ute Indian was taken prisoner without any rights in a conflict that the local Native Americans were trying to avoid. The young children who were forced to stay there for a month had bitter memories for the rest of their lives on the fence.

Meanwhile, Posey and the others make their way to the safety of Bears Ears and Comb Ridge. Utes fled in several directions and a large militia assembled by the sheriff was told by him: I want you to film anything that looks like an Indian.” Posey fought back in self-defense as he fled to a country he knew well.

Bill Young saw Joe Bishop’s boy and Sanap’s boy running fast towards him. He hid in a low tree because “they came at full speed on horseback about 15 to 20 feet away, got up in their stirrups, thought I was still running, and drove me down the slope. Because I was looking for it.” Young drew beads on the nearest Joe Bishop’s Boy. “When he was where I could see the button on his shirt, I took the bead on his third button and pushed the trigger… when I last saw him, he was still sitting in the saddle. ‘ Joe Bishop’s Boy died of his injuries.

Over the course of the day, Blanding’s militia joined the Bluff militia, and as the unarmed natives awaited transport after marching up the Comb Wash, more Utes were rounded up by the guards and ordered to be shot. was given. The day before, Bluff militia leader RL Newman, a former sheriff of Navajo County, Arizona, issued orders for his belongings while searching for Mesa Top.

“Now, folks, let’s mark this vertex,” he said. “Comb carefully and shoot only the Indians. Then shoot them dead.”

While Posey was hiding, his relatives and friends were aware of his whereabouts and brought him food.

“The first night we camped at Comb and sent out the Indians with a herd of mules and food and blankets to scout and try to find Posey. “I went out a few times and each time I came back without food.”

The Utes knew Posey’s location because they used signal fire from cedar bark torches.

The deputies interrogate the captured Yute, demanding to know Posey’s whereabouts. Posey’s relatives never revealed where he was hiding. Posey, who fled to the other side of the west, died alone near Mule Canyon, while 80 Ute friends and relatives remained behind the barbed wire of Blanding. He died in the canyon where his ancestors lived for centuries, just a few miles from the Bears. He died resisting a white invasion of his traditional Ute homeland.

The inhabitants of Blanding have taken the law into their own hands. After all, Native Americans didn’t have citizenship yet, but they were finally granted citizenship in 1924.

“We built a barbed wire fence called the ‘bullpen’ and put Pinon in there as a bunch of slaughtered oxen,” said Branding founder Albert Lyman, referring to the Ute people. Mentioned like grazing cattle.

Freed from the stockade, Merciful Yute recovered and reburied Posey in an unknown location near Bears Ears. He was shot and died of septicemia and infection, or at least that’s the standard ending to this salacious tale.Utes felt otherwise. They believed Posey was killed by poisoned flour provided as a food ration.

That March of 1923, the Utos huddled around a small fire and sheltered in two Navajo hogans built within the stockade. Occasionally, prisoners were allowed to go off to herd scattered livestock on traditional Aboriginal lands. Posey never gave up.

“The settlers couldn’t find him, so they mixed poison into a bag of flour so that people who were freed from the fence and caring for Uto’s animals would give it to him,” McPherson said. Myers Cantosy, Posey’s sons Anson and Jess, Marshall Ward, Jim Mike, and Jack Fry found Posey’s dead body. his dog was dead. He was cooking on the campfire and the wound on his thigh appeared to be healing.

“Posey made biscuits out of flour, fed them to his faithful dogs, and ate them himself,” said Francis Posey.

“Later, after settlers found his corpse, they say they shot it so they could claim it was the cause of his death, but the white flour and bread in his hands were what actually happened. “It showed what it was like,” McPherson said.

Perhaps it’s just folklore, a native story to maintain Posey’s reputation as an unbeatable leader by the whites. I discovered that there was poisoned bread left in the hut. It had the deadly intent of harming or killing natives if they stole food from ranchers’ stashes. Somewhere between the bullet in the hip and the bread in the dead man’s hand is the truth.

We hiked the Posey Trail off US Highway 95, which bisects San Juan County and runs under Bears Ears. The trail zigzags uphill across Slickrock and leads to Pinon Pine as it climbs even higher to the heights of Comb Ridge. There was a small saddle or flat area at the top where a dozen people could camp with a view to the west. What was it like being chased by angry men and ordered to shoot?

Watching small cedar torches at night, I knew where Posey and his followers sought refuge. Early the next morning, the troupe raced up the trail, but Posey’s group jumped off the escarpment of Comb-His Ridge, prompting the horses to jump off the sandstone ledge. Utes and his fearless pony escaped. Posey hid. He bears his ears lying somewhere in the sacred aboriginal landscape. A century later, Comb’s backtrail from his ridge is impossible to discern, but his memory remains as strong as his bones.

Note: This column is an excerpt from Andrew Gulliford’s new book Bears Ears: Landscape of Refuge and Resistance (University of Utah Press, 2022).

Award-winning author and editor Andrew Galliford is Professor of History at Fort Lewis College. Please contact andy@agulliford.com.

The backwaters of San Juan County, Utah, in the early 20th century are represented by this map, published in 1910 by archaeologist Byron Cummings in The Ancient Inhabitants of the San Juan Valley. Note that the rocky San Juan He Triangle, or the area between the San Juan and Colorado rivers, is labeled “unexplored.” Bears Ears is Orejas del Oso in Spanish. (Photo credit: Andrew Galliford)

Posey hid in the Bears Ears region, probably in the upper reaches of Mule Canyon. The U.S. Marshal claimed Posey died from a gunshot wound to his hip.Ute’s family believe Posey was fed poisoned flour. He baked biscuits for himself and his dog, but both were found dead. (Photo by Andrew Galliford)

Utah Branding does not have descriptive signs marking where members of the Utah Tribe were forcibly arrested and imprisoned, but in San Juan County, parking is easy from Highway 95 and recently installed We are promoting the Posey Trail that will take you through the gate. barbed wire fence. This photo is from the top of the Posey Trail overlooking the Comb Wash with Bears Ears and Elk Ridge to the west. (Photo by Andrew Galliford)