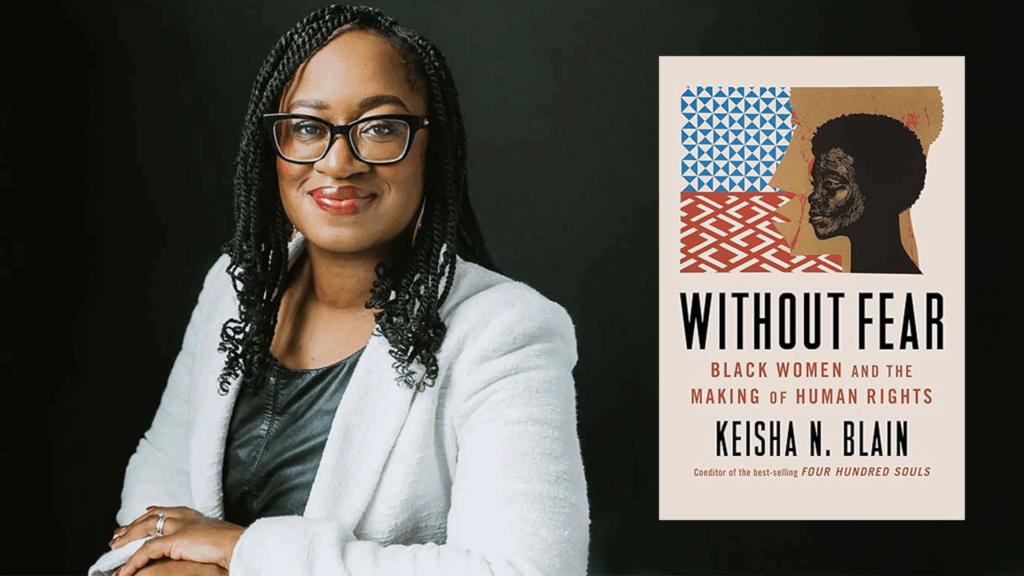

Keisha N. Blaine’s New Book on Black Women and Human Rights

In her new work, “No Fear: Creating Black Women and Human Rights,” Keisha N. Blaine, a historian and author, explores the crucial yet often overlooked contributions of African-American women in the development of human rights, both in the United States and around the world. Notably, many of these women’s experiences share a link—Alabama.

From Pearl Sherrod, whose background as the daughter of a farm laborer near Montgomery shaped her experiences, to Esther Cooper Jackson and Dorothy Burnham, who worked with the Southern Negro Youth Congress, Alabama is a recurrent theme in their narratives.

I recently chatted with Blaine to gain insight into how Alabama influenced these women’s actions and perspectives, as well as how their stories remain relevant to people in Alabama today.

“Alabama has historically been a significant site for black political organizations,” Blaine remarked. “Given its past, the circumstances weren’t easy for Black Americans. They faced immense challenges like Jim Crow laws and racial violence. Yet, despite these severe obstacles, the movements of the 1950s and 60s emerged.”

Blaine emphasized that the book showcases the various strategies used by women of that era to enhance conditions for Black individuals. “One essential space was the Black Church,” she noted, “where women could collaborate to broaden opportunities and challenge segregation. This often involved legal action, with organizations like the NAACP playing a vital role, making Alabama an important site for strategic development.”

She highlighted Pearl Sherrod’s story as a prime example of how the hardships faced by Black women in Alabama during the 19th and 20th centuries fostered political activism.

“Pearl Sherrod is interesting because she didn’t affiliate with mainstream organizations like the NAACP or Urban League,” Blaine explained. “Growing up in a rural area southwest of Montgomery, she wasn’t involved in politics early on. But Alabama provided a backdrop where she could evolve into a politically aware individual, confronting not just local issues but global ones.”

“Her upbringing was significant,” Blaine continued. “She lived on a plantation and belonged to a large family where she had to contribute to their survival. Growing up in poverty, she focused on basic economic issues, a mindset that I think stemmed from her class background. Her struggles with financial injustice were constant, and she later moved to Detroit, getting involved with various radical activists in the 1930s.”

Blaine sees Sherrod’s experience as a reflection of how the Jim Crow South compelled women facing daily discrimination and violence to become politically engaged.

“The environment was undoubtedly challenging for women,” she added.

Other figures like Esther Cooper Jackson and Dorothy Burnham also sought to confront segregation head-on, fueled by their commitment to human rights and a more radical political agenda, even as they moved beyond Alabama. Their work with the Southern Black Youth Congress, in collaboration with Communist groups based in Birmingham, influenced their future roles. Although both eventually left Alabama, their time there was foundational for their involvement in Freedom Way, a key publication for Black activists during the Cold War.

Blaine posits that pioneering women like Sherrod, Cooper Jackson, and Burnham exemplify how individuals can enact significant change even amidst systemic disadvantages.

“Their stories highlight how one person can truly impact their surroundings,” Blaine noted, adding that they illustrate the struggles faced by Black women who weren’t even recognized as full citizens at the time, lacking access to voting and facing numerous hurdles. Yet, they remained steadfast in their pursuit of rights not only for themselves but for all marginalized groups.”

Blaine points to the well-known Scottsboro case, where nine Black teenagers were wrongfully accused of raping two white women in 1931, as another instance of women’s activism in the face of injustice. “Women organized around the Scottsboro incident, both locally and nationally, creating avenues to raise awareness about Alabama events and advocating for broader societal changes,” she said.

“Reading these accounts can inspire action, especially for those feeling powerless today due to diverse challenges,” she remarked. “These stories show how small shifts can lead to significant change. Many of the challenges these women faced resonate with present-day struggles, perhaps prompting readers to adopt similar strategies.”

“No Fear: Creating Black Women and Human Rights” by Keisha N. Blaine is currently available from WW Norton & Company.