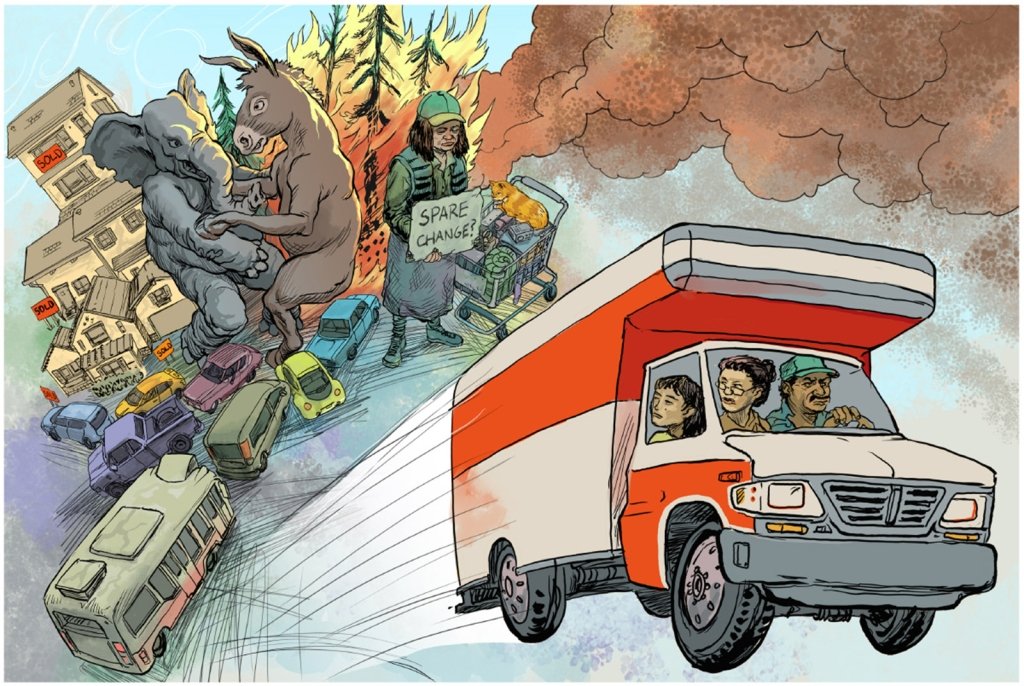

One of the reasons for California’s declining population is that people can work from other states where housing costs are lower. (Illustration by Jeff Durham/Bay Area News Group)

The topline numbers were eye-popping: 725,000 people Leave California in 2020 and start a new life in one of the other 49 states or in Washington, D.C.

If this were the end of the story, the numbers (derived from the Internal Revenue Service’s 2021 immigration data) would represent the largest single-year exodus in state history.

But it didn’t end there. California’s population has been steadily declining since 2020, although experts say the reason is more subtle than a single year’s total outflow. According to recent state data, California’s population has fallen from 40 million just four years ago to just under 39 million today.

Lots of other new data shows where people are headed (Texas, Idaho, Florida, and neighboring Arizona and Nevada). Opinion poll reports show who will retire (high-income, well-educated workers are now joining a migration pattern historically dominated by low-income workers). Yet another data shows that at least some of the financial and social challenges causing problems in California (rising house prices, stagnant wages, crime) are not that different even in the state with the most California ex-citizens. indicates that there is no

“I didn’t think I’d miss it. And in many ways, I was right. I’m not,” said Debbie, who moved from Burbank to Boise, Idaho, last year with her husband and three children. Higby said with a laugh.

“But I’m not one of those people who hates California,” she added. “It’s all really incomprehensible.

“For me, it’s fine there. Things aren’t perfect here either. Both places have their pros and cons.”

Blip or trend?

The outflow of 725,000 is a high-end figure, not a net figure. But California’s actual internal immigration in 2020 lost about 331,000 more people to the state than those returning from other states, making it a boon to those who follow the situation closely. I thought it was going to be tight.

“Yeah, it’s big,” said political scientist Eric Magee, a senior fellow at the California Public Policy Institute and co-author of a blog on state politics, demographics, and other issues related to California’s population. He said.

But McGee, like others studying California, was quick to add: For at least the past 30 years, California has exported more people to other states than it has imported. ”

In fact, McGee’s blog tracked last year’s monthly data and found that from July 2021 to July 2022, California lost about 407,000 people to other states, and this is arguably the biggest change in state history.

“We’ve had some years in the last few decades where we’ve had net gains, but the typical result is losing people,” McGee said.

But more people from all over the world move to California each year than to places like Texas or Idaho, and it’s also typical for domestic outflows to be offset by international inflows. In 2020 that was not the case.

And for most of the year, state residents weren’t shocked by the pandemic’s rise in deaths and the associated drop in births. And thousands of employers across the state each year impose massive layoffs in a relatively short period of time, then rehire at a breakneck pace, eventually ending up with millions of workers anywhere in their homes. never decided to let workers work from home. Might be so. All of this happened in the first year of the pandemic.

The bottom line: California’s population in 2020 not only grew more slowly than before, it actually decreased by nearly 359,000. The same thing happened in 2021, with California’s population down by 114,000.

The pandemic has since ended, but California’s declining population has not.

The contraction continued last year, with about 139,000 deaths in the state, according to California Treasury Department data released this month. State officials now estimate California’s population at about 38,940,231, falling below 39 million for the first time since 2015.

All this raises the question: spike or trend?

“The state is predicting growth will resume,” McGee said.

Over the past year, immigration has started to rise and pandemic deaths have fallen. But fertility rates haven’t fully recovered yet, and the once-unexpected rise in out-of-state office workers working from home makes the rise of former Californians like Higbee and her family all the more important. It has become.

In its May 1 report on the state’s population, the California Department of Treasury said, “Net internal migration is offsetting natural growth and migration growth.”

That said, as McGee pointed out, the state predicts that population growth could resume as early as next year and could exceed 42 million by 2030.

“Let’s see,” McGee said.

green grass?

Years of public opinion polls by the Public Policy Institute and others have found that people from California cite similar reasons to move, including housing prices, family and work.

And for many conservatives, politics.

In a PPIC survey last year, 56% of those who said they disapprove of Governor Gavin Newsom also said they wanted to move out of California, compared to 28% of Newsom supporters who said the same. . This reflects a nationwide progression for much of this century in which people moved closer to those of similar political beliefs, a trend some demographers describe as “big kind”

But the “migration” of data suggests that politics is the motivation for some, but not all.

According to the 2020 IRS Immigration Report, the most popular state for ex-California is by far conservative Texas. It was also found that among ex-California, bright red Idaho was fourth, and red Florida is now fifth.

But the second-highest-profile state was Arizona, which voted for Democrat Joe Biden in 2020 and is generally considered a mixed state politically. So does Nevada (which is also politically mixed) in third place. In 2020, only three counties across the country had more than 1,000 California residents: Maricopa County, Arizona (Phoenix), Clark County, Nevada (Las Vegas), and King County, Washington (Seattle), all of which were Republican. There are more Democrats registered than members.

Higby, who moved to Boise from Burbank last year, said politics had nothing to do with their move.

“Actually, I’m not a fan of politics here. It’s kind of crazy. But I haven’t always liked California politics either,” she said.

“I wish it hadn’t happened at all.”

Instead, Higbie’s move was about house prices and because she could keep her job by working from home as long as her husband commute to California once a quarter.

The median home price in Higbie’s new county, Ada, Idaho, was $492,000 in April, compared with about $1.1 million in her former home of Burbank, according to data.

“We can change lives,” Higby said. “So we did.”

But long-term data compiled by USA Facts using information from the U.S. Department of Labor and the Federal Housing Finance Agency show that life-changing real estate values won’t last forever.

Since 2015, home prices in Ada, Idaho have risen 136% and wages have risen 44%. During the same period in Los Angeles County, home prices rose 68% and wages rose 36%. And at the state level, the gap between house prices and wages is widening in all five states that attract more Californians than California.

Another factor for the Higbees, and hundreds of thousands of others if the data is to be believed, is taxes.

Three of the five largest states Californians migrate to (Texas, Nevada, and Florida) have no state personal income tax, while the other two (Idaho, flat 5.8%; Arizona, flat 2.5%) do not. Lower than state personal income tax. Parts of California range from 1% to 12.3%.

But personal income tax is only part of the picture. Considering the variety of ways states extract money from their residents, from property and sales taxes to license fees, every destination state is looking to make up the income tax gap, according to a Census Bureau report. It says.california overall tax burden The highest at 9.2% of median income, but Nevada 8.3%, Texas 8.2%, Idaho 7.9%, Arizona 7.7% and Florida 6.7% are all within screaming range.

Still, if the Higbies represent the future in any way, it may be their experience as interstate telecommuters.

McGee said it’s too early to know how much impact long-distance telecommuting has had on recent immigration patterns, but it could reduce California’s population going forward.

“Historically, it was the low-income population who were most likely to leave California. said.

“But what’s changed during the pandemic is that high-income people have also started leaving their homes, and many of them did so because they could still keep their jobs in California.

“This is a big part of the acceleration of internal migration,” he added.

“Maybe in the future.”