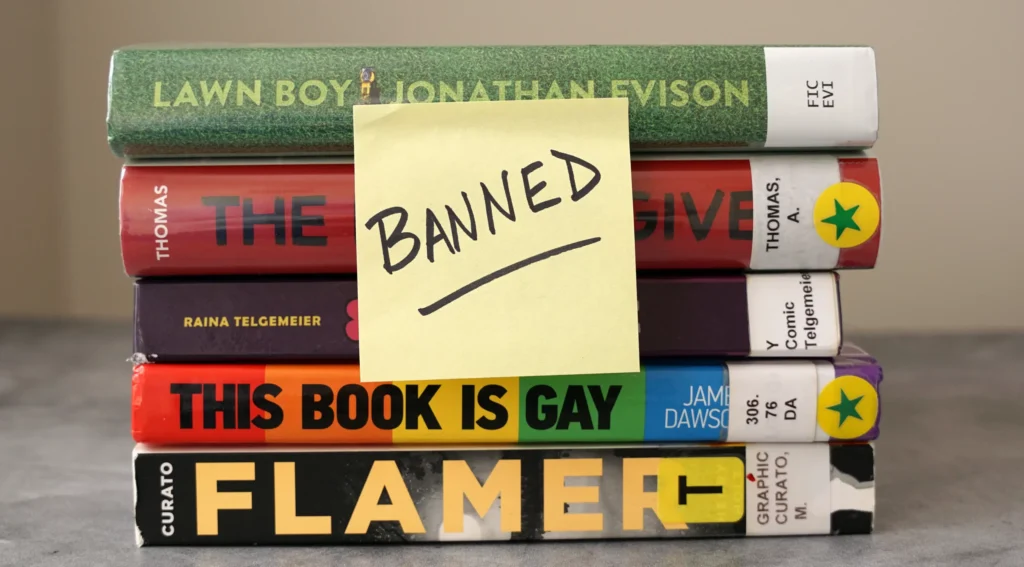

Concerns Over Book Removal Laws in Florida and Alabama

Recently, I shared thoughts on a federal judge striking down a Florida law that allowed schools to remove books labeled as containing “sexual conduct.” This made me ponder if I should further discuss how it connects to Alabama’s situation, or maybe I was just reiterating previously covered ground.

Then I came across an opinion piece by Laura Clark, a librarian from Autauga-Prattville, published on 1819 News, a far-right media outlet. It seemed to counter my article and, frankly, misrepresented it. If someone with her legal background, who claims expertise in constitutional matters, got it wrong, I figured it was necessary to clarify my points for those who might not be as informed.

In my view, a crucial takeaway from US District Judge Carlos Mendoza’s ruling is how the government’s ability to restrict minors’ speech hinges on what’s known as the Miller for Minors Test.

This test draws from the Miller Test established by the US Supreme Court in 1973 and includes three criteria to determine if material is indecent. The Miller-for-Minors test evolved from the case Ginsburg v. New York, providing a tailored version to assess the distinct differences between minors and adults.

Essentially, this test defines what is considered “harmful to minors,” a concept already embedded in both Florida and Alabama laws. In Alabama, Representative Arnold Mooney from R-Indian Springs has been trying for about three years—though it seems overly complicated—to keep books promoting gender diversity away from minors in libraries.

If a book about transgender individuals for children gets removed from the minors’ section under Mooney’s law, it could provoke lawsuits centered on the first prongs of the Miller for Minors Test if it eventually passes. Many challenged books at the Alabama Library, which include stories about transgender experiences, barely, if ever, touch on sexual topics. This makes it hard for the state to argue that removing these texts caters to an inappropriate interest in sexuality, especially when taking a broader view.

Additionally, the Alabama Public Library Service Code may find itself at odds with this ruling. There are nuances within APLS since it doesn’t overtly ban books but rather restricts them based on funding decisions. If the mandate is deemed unconstitutional, it could violate the “doctrine of unconstitutional conditions.”

This mandate mirrors Florida’s legislation, permitting the removal of books centered on “sexual conduct” without consideration for what is “harmful to minors.”

From Mendoza’s perspective, Florida’s law is clearly unconstitutional. He stated, “The ban on content that ‘describes sexual behavior’ or is considered ‘pornographic’ fails to meet the necessary specificity to categorize obscene material.” Since Florida’s laws already prohibit obscene material for minors, this new legislation risks violating First Amendment rights.

Mendoza emphasized that the only comprehensive ban the government can impose on library materials for minors aligns with the Miller for Minors Test. However, the APLS code sidesteps this requirement, neglecting to assess whether the material has literary, scientific, artistic, or political relevance to minors. Rejecting all explanations of sexual conduct, regardless of context, represents an overly broad approach. APLS Chair John Wall attempted to define “sexually explicit” by referencing federal child pornography laws, but this doesn’t adequately address the First Amendment issues.

Mendoza described Florida’s legal stance as “confusing,” pointing out that the law not only fails under rigorous scrutiny but also does poorly under more lenient standards.

Clark’s opinion seems to overlook the direct reference to the Miller for Minors Standard in both my article and Mendoza’s ruling. Yet, she claims that the concept was “completely skipped by Mendoza and APR.”

It’s disheartening that lawyers involved with our libraries either haven’t properly interpreted the verdict or have misunderstood it, and it’s troubling that legal arguments like Clark’s could lay the groundwork for unconstitutional censorship in both Alabama and Florida.