In a decidedly controversial 42-page ruling, a civil court judge effectively blocked the county oversight agency’s sweeping investigation into deputy gangs operating within the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department.

The lengthy ruling, dated Monday and announced the next day, follows an ongoing lawsuit over whether alleged gangster suspects can be compelled to answer questions and show tattoos to county supervisory investigators. was the latest development of

Assn. The Los Angeles deputy sheriff, who filed a lawsuit in May, said that requiring members to expose ink or submit to interviews would be a violation of the Fourth Amendment’s ban on unjustified searches and the Fifth Amendment. It said it violated the article’s self-incrimination protections, as well as state labor laws.

Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge James Chalfant also agreed in part, so far. But it was the debate over labor law that he found most persuasive, so this week’s interim injunction simply suspends the Inspector General’s investigation until the labor issue is resolved.

The judge said there was no urgency to proceed with the investigation immediately, given that the county’s subordinate gang investigation has already taken time.

“Because tattoos are permanent and can be inspected after trial on the merits, the county suffers little or no harm from a preliminary injunction,” Chalfant added.

Still, civil rights experts fear the decision could have far-reaching ramifications for efforts to hold law enforcement to account, effectively undermining a 2021 state law aimed at cracking down on gang sub-organizations. are doing.

“It can have a chilling effect,” said Andres Kwon, a senior policy adviser at the American Civil Liberties Union in Southern California. ” The law requires all law enforcement agencies Clearly prohibit the representation of organized crime groups, and basically cooperate with the investigation of the representatives of organized crime groups. This is a clear obligation and ALADS is trying to block the enforcement of this law. ”

In Los Angeles, the ruling poses a serious obstacle to the Inspector General’s investigation.

Inspector General Max Huntsman said, “It’s unfortunate that the Gang Deputy remains for the foreseeable future. We expect the county to appeal.”

He added, “It’s been a year and a half since California outlawed gangs without a meaningful law enforcement investigation.” “My office will continue to work towards the day when the Sheriff’s Department can no longer ignore the law.”

The sheriff’s department withheld comment from the county attorney, and the county withheld comment from the inspector general. ALADS President Richard Pippin said the union was “glad the court has issued the injunction,” but declined to comment further before reviewing the full document.

The verdict was a disappointment to the families of those killed by the sheriff’s deputy.

The verdict is honestly not surprising,” Stephanie Luna said. His nephew was murdered by lawmakers in 2018. “But this is worrying because no matter what lawmakers do, the system will always work to protect them.

For nearly half a century, the Sheriff’s Department has been plagued by corrupt groups of lawmakers who allegedly engage in rowdy behavior in certain stations and promote a culture of violence.Loyola Marymount University report has been published In 2021, 18 such groups that have existed over the past 50 years have been identified and are commonly known by names such as: executioner, banditRegulators and Little Devils.

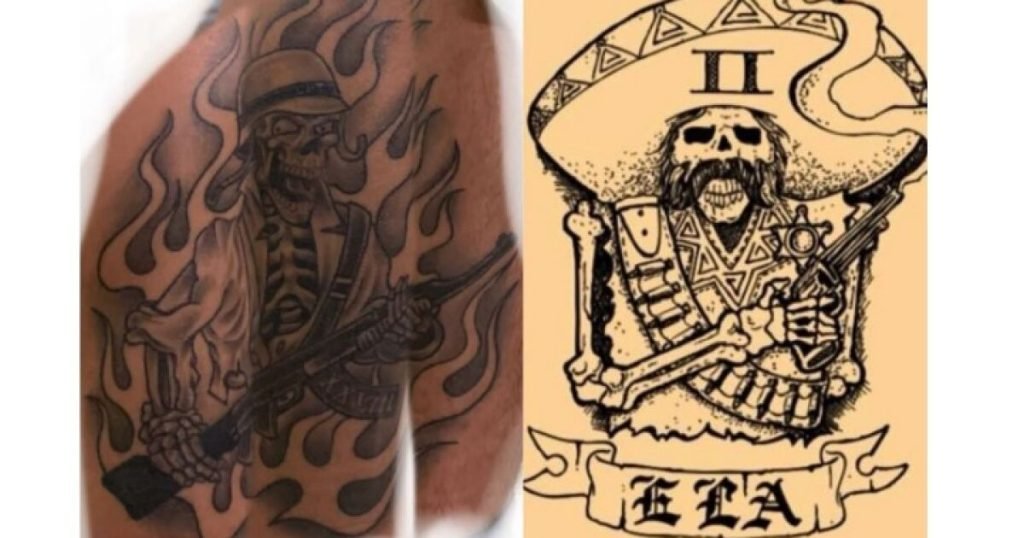

The members of the groups are identified by matching consecutive numbers, such as a flaming skeleton wearing a Nazi-style helmet associated with the Compton Station Group and a skeleton wearing a sombrero with ammunition and a pistol associated with the East Los Angeles Station Group. It is claimed that he has a tattoo.

Before being ousted last year, then Sheriff Alex Villanueva repeatedly denied the existence of such groups, obstructed the Inspector General’s investigative efforts, ando Ban the Huntsman from Department facilities and databases. Restored Huntsman access after Sheriff Robert Luna became the county’s top police officer in December, Vowed to ‘eliminate all secondary gangsters’ from the department.

In May, the Inspector General’s Office sent letters to 35 lawmakers suspected of being members of a group commonly known as the Compton Station Executioners, or the East LA Station Banditos.

The letter ordered lawmakers to appear in court and show their tattoos, to reveal the names of other lawmakers with similar inking, and to question whether they had ever been invited to tattoo-related groups. was The ultimate goal was to produce a list of all deputy gang members in the department, Huntsman said at the time.

Initially, it was not clear whether refusal to cooperate would have any repercussions. Luna then sent an email to the entire department telling staff that they could be reprimanded or fired if they did not comply with the inspector general’s request.

In response, ALADS filed the following complaint: Labor Complaints and State Court Litigation That led to this week’s temporary injunction.

Initially, Chalfant issued a temporary restraining order in late May to prevent the county from forcing lawmakers to answer questions or show their tattoos. And in late June, a judge heard discussions from the county and unions about whether the terms of the restraining order should be maintained as an injunction or should be allowed to proceed with the inspector general’s investigation.

In court, the judge repeatedly expressed concern over the swirling allegations surrounding the deputy gang leaders, saying some of them sounded like “criminal acts”. He also questioned whether the Fifth Amendment protection against self-incrimination really applies because it is not illegal to belong to a law enforcement organization. Even if it could be grounds for dismissal.

Union lawyers argued that forcing lawmakers to show their tattoos, even if they lifted one leg of their pants, constitutes an “unfair investigation” that violates the Fourth Amendment. County attorneys said they narrowed the proposed investigation to focus on visible tattoos such as the face, neck and below the knees. They also questioned why it would be unconstitutional to show legs “unless you absolutely wear shorts.”

Lawyers for the union also said the new state law requires law enforcement to cooperate with the inspector general’s investigations, but counties must negotiate the content and procedures of such investigations before ordering lawmakers to follow them. said there is.

County attorneys said there was “fundamental disagreement over whether there is a duty to negotiate” at this point in the proceedings, and the judge said the law does in fact require lawmakers to cooperate with the investigation. He questioned whether it was mandatory to have the sheriff’s cooperation or only the sheriff’s cooperation. As a representative of an agency.

After hearings last month, the judge spent about two weeks weighing the harm of blocking an investigation against the harm of potentially violating labor obligations.

“The damage to the public from gang activity is enormous and weighs heavily on balancing the interests affected by the preliminary injunction,” he wrote. “LASD delegate gangs also damage the county by undermining public confidence in law enforcement, weakening chains of command, promoting racism, sexism and violence, and intimidating other legislators. It is a serious responsibility of the county.”

But Chalfant said the county has a legal obligation to negotiate with the parliamentary union before introducing major changes, such as requiring lawmakers to show tattoos. And since the tattoo is permanent and the county law enforcement agency has settled in a “red tape process” that will take time, Mr. Chafant has voiced his support for lawmakers and their labor issues. .

“The OIG is certainly frustrated by the delay, but there is no immediate need to investigate,” Chalfant wrote.

Both parties are scheduled to appear in court again in September.

Times reporter James Query contributed to this report.