It was like any other night. Silverio Lujan’s teenage daughter was aloof and lethargic. And, unbeknownst to him, she has a handful of drugs and a knife in her hand and threatens to end her life.

In a panic, he called 911.

After the diagnosis, a local non-profit intensive care team quickly intervened with Lujan, 34, and his 13-year-old daughter. From the February episode he spent three months with the team fitting into his family’s life in South LA. Both father and daughter went to therapy.

They are still working on the issue, but the crisis is over.

Lujan said in Spanish that her daughter’s therapy has “changed her and made her want to be closer to her family, learn things and keep fighting for what she wants – her dreams.”

But the program that Mr. Lujan claims to have saved his daughter from suicidal depression has now ended. His family were among the last to receive the service.

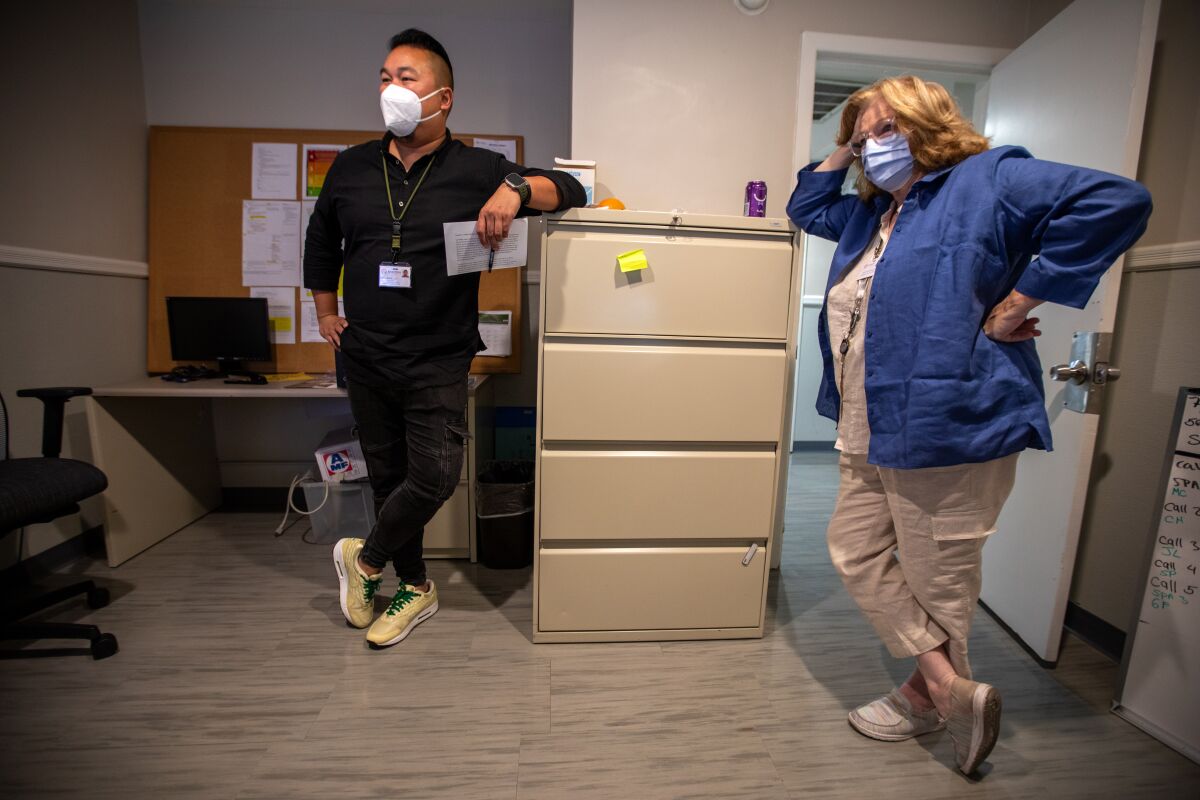

Staff at the Children’s Institute in Los Angeles are pictured in a picture frame discussing the closure of a mental health program aimed at connecting vulnerable people to care.

(Luis Cinco/Los Angeles Times)

Providers claim that so-called child and adult outreach triage teams are helping some of Los Angeles County’s sickest residents by bridging care gaps.

But officials with the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health said they were underwhelmed by the team’s performance.

The program was funded by two state grants totaling approximately $30 million, funded from taxes imposed on billionaires by voter-passed mental health services laws. The subsidies expired in June. The county refused to use its own funds to continue services. By the time the program ended, the county had spent only about half of its state funds, according to preliminary statistics. An estimated $15 million will be returned to the state.

This large amount of unspent funding represents a “debacle,” said Dr. Jonathan Goldfinger, a pediatrician who previously co-chaired the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health’s Alternative Crisis Response Initiative.

Goldfinger described what he called a history of backsliding within the mental health sector, often driven by internal politics related to staffing.

“What a man will have [that much money] To serve and give to those who are suffering? It’s not good for me as a doctor, as a public health professional, or as a human being,” said Didi Harsh, former CEO of Mental Health Services, now in physical and behavioral medicine. said Goldfinger, a system consultant.

Alex Briscoe, former director of the Alameda County Health Services Agency, said disbursement of funds can be difficult and slow, and partly due to the boom-bust nature of California’s public revenue streams, the county remains committed to its financial commitments. said he was afraid to He is currently the principal of the California Children’s Trust, a policy advocacy group.

Los Angeles police have been dispatched to assist a mobile crisis response team staffed by mental health professionals in dealing with a man in the midst of emotional distress.

(Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

The controversy over the treatment of Los Angeles triage teams highlights how counties in California fund mental health services, which temporarily fund new ideas. It is often abandoned after county leaders fail to come up with a plan to maintain it before the funds are exhausted.

The system may be reworked in the near future. Governor Gavin Newsom recently proposed a review of key funding sources for local mental health departments. Some stakeholders see the move as an attack on how the funds generated by the Mental Health Services Act are handled by county governments and the boards that oversee the funds.

As homelessness and mental health crises overwhelm local systems, the governor has proposed shifting resources to address the urgent need for beds for those suffering from serious mental illness and substance abuse problems. ing.

Given limited resources, a focus on housing and treating critically ill patients will almost certainly mean less budget spent on prevention programs as well as triage teams, said Briscoe. rice field.

“For many people, [what] I’m concerned about prevention, kids, it’s going to be a big deal,” Briscoe said. “But I totally understand how we got here.

The city of Los Angeles won a grant to launch a triage program in 2018, but it didn’t begin until late 2020. The county originally intended to provide the service directly, but chose to outsource the work.

Triage teams were created to prevent emotionally disturbed people from being sent to hospitals and prisons. The idea was to help people when they needed it urgently and then help them connect to long-term service.

To do this, three mental health professionals step into the individual’s world and meet where the person is, often on a street corner or living room. They then embark together on a journey to access care in an often opaque system, plagued by waiting lists that can stretch for months, supported by team members and often family members.

“We would go out on the streets with them during the day, work with them, talk to them, and they would think of us in the world. So we have fewer phone calls in the middle of the event. It’s night,” said the team overseeing the nonprofit Children’s Institute, one of six providers contracted by the county. said Deedee Hitchcock.

During her nearly 23-year tenure, she has seen countless pilot programs come and go, but said she knew this would continue.

“This was something special,” Hitchcock said.

In recent years, county officials have worked to strengthen mental health crisis response services, in part due to federal mandates. Last July, a national mental health hotline, known as 988, went live and began an effort to develop a new emergency plan for people in distress.

Lewin Kwan, a certified clinician (left), and Suzanne DeWalt, a peer support specialist, wait to be called to help those dealing with mental health issues at Sycamore’s in Altadena.

(Francine Orr/Los Angeles Times)

Hitchcock said many services, such as crisis calls and mobile teams, are reactive, waiting for a fire to break out and then rushing to extinguish it. In contrast, the triage team aimed to prevent.

Other programs “do not actively care for them in the community and actively weave safety nets,” Hitchcock said. “That’s the big missing piece.”

Josefina Cignale, a former caseworker in the program, recalls one client. The man, a middle-aged man who had endured trauma his whole life, reportedly told team members that he repeatedly contemplated suicide while walking about four miles to the Children’s Institute campus in Westlake. , just west of downtown Los Angeles.

“‘Should I jump off this bridge?’ Should I walk through the traffic?’ Because I made a promise to you,” he said. And I had to defend it,” Cignale said.

But Jennifer Holman, alternate crisis response manager for the mental health department, said department officials were unimpressed by the number of adults and children the triage team connected to services.

According to the Department of Mental Health, just over 15% of adults referred to the program in fiscal 2021 led to new mental health services, rising to 33.5% for children.

“We knew the program needed a better way to engage with the person afterwards,” Holman said.

Children’s Institute president and CEO Martin Singer questions the validity of the measurement.

Many people who referred to the program were never contacted. While finding adults with severe mental disorders living on the streets can be particularly difficult, health care providers said children tended to have more engaged caregivers to facilitate connections.

In October, knowing that the grant was about to expire, Singer wrote to the county’s Department of Mental Health asking them to continue the program after the state’s funding ran out.

Lisa H. Wong, now head of the department, said the team’s situation was “complex” but would consider the proposal.

As of February, the provider had yet to answer whether the program would continue. Singer sent an email emphasizing the urgency, and another 10 days later.

Without the program, “it’s hard to imagine what would happen to all the people we help, especially adults with mental disabilities,” Singer wrote in a Feb. 11 email. “Let’s not return to a world where those who need it most fall through the cracks of a broken system.”

We got the answer in March. The county stopped referring children and adults to the triage program, a step toward discontinuing the triage program.

County mental health officials and providers are divided as to why the county put so much money on the table.

Department of Mental Health officials said the difficulty of hiring and retaining staff made it difficult to ramp up the program quickly.

Top staff at two of the contract providers did not see hiring as an issue. Instead, the ministry did not allow referrals from various sources, including schools, hospitals and police stations, he said. That would have greatly increased the number of people who could help.

The ministry acknowledged limiting referrals because of subsidy requirements, but did not provide detailed answers to questions about the nature of the requirements.

County mental health officials said they were looking to extend the grant in January. The state had already extended the subsidy from three to four and a half years, but refused to extend it any further.

The county could have continued the program with other funding sources, according to the State Mental Health Service Oversight Responsibility Board.

“We want counties to put their money to good use, and that good use is reflected in the fact that they are willing to keep it with that money,” said Commissioner Toby Ewing.

The county now says it hopes to leverage its existing mobile crisis response teams to provide similar services.

Staff at a children’s institute in Los Angeles discuss the closure of the mental health triage team they operated.

(Luis Cinco/Los Angeles Times)

“Although the grant is ending, the county is committed to ensuring these critical efforts continue, and these critical follow-up and collaborative services are being incorporated into our mobile response teams and alternative crisis response efforts. ,” said Los Angeles County Superintendent Hilda L. Solis. said in a statement.

“This will allow us to leverage other state and federal funds to support these services and will strengthen my efforts to expand housing and services throughout the county.”

A Times survey earlier this year found that these mobile crisis teams were struggling to expand, with people in dire situations waiting hours for help. In 2022 he was over a third of the time, and the team took him over eight hours to respond to a crisis call.

Connecting people to care can be a huge feat. It’s unclear how the team will assume that responsibility.

“Certain facilities and services are so overburdened that sometimes it makes me sick just to mention it, knowing that you’ll have to wait two years,” the hospital said. said Lewin Kwan, a mental health clinician on the mobile crisis team that provides the service. “And they are seeking immediate relief,” the county said.

This article was produced as part of USC Annenberg health journalism centerThe 2022 Data Fellowship and Engagement Initiative. The Center’s California Engagement Editor, Cassandra Garibay, provided the Spanish translation.