The requirements for living on San Fernando Valley property were clarified in 1915.

Buildings, including the roof, should always be painted twice. Fences “shall” be stained, painted, or whitewashed.

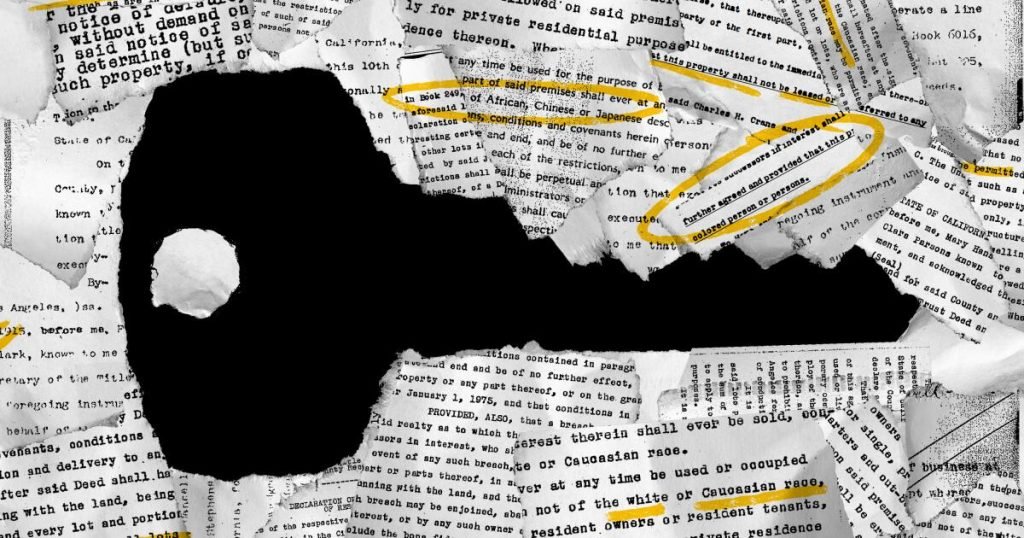

Land records for the Los Angeles Agricultural and Milling Company Rancho subdivision, which was negotiated shortly after alcohol sales prohibition, state that “no portion of the property shall be sold, transferred, leased, or rented to any person under any circumstances. It must not be lent out.'' They are of African, Chinese, or Japanese descent. ”

Such racially restrictive covenants were common in Los Angeles County in the early 1900s, but were abolished only after the U.S. Supreme Court and federal law prohibited their enforcement. But now in L.A. County, if he bought a home built before 1968, it would probably still have that language listed in the land records. But that will soon change.

In response to new state lawLA County is hired a company It spent about $8 million redacting racially restrictive code language from millions of county records. The process is expected to take at least seven years and will begin this year.

“This is part of the stain on our history of discrimination and racism,” said Dean C. Logan, Los Angeles County Registrar-Recorder and County Clerk. “I think this represents some kind of recognition for me and for the county.”

Logan said the county will work with Extract Systems, a Wisconsin-based company, to search and examine the entire archive, which dates back to 1850.

An estimated 130 million documents (about 460 million pages) will be examined, Logan said.

Approximately 90 million of these documents are in digital format, allowing contractors to use automation to look for racist language. But the rest of his 40 million records are from 1850 to 1976 — Recorded only on paper, books, or microfilm rolls. Logan said redacting racist language from these documents would require “human operators and the use of technology.”

Employees start with the most recent document in digital format and work backwards. Logan said the original document will still be available for viewing, but the version viewed by property owners will have a black bar over the language.

The seven-year schedule is based not only on workload, but also on how much money the county brings in in new $2 documentation fees. The fee is allowed to be charged until 2027 unless extended by state law.

For years, homeowners have been able to request that counties remove racially restrictive covenants from their records for free. That process is still available.

“Carrying that language in a legal description into a future document is almost a passive acceptance of it, and those restrictive covenants have been outlawed and cannot be used in future documents in the chain of title. has no useful purpose,” Logan said. “I think the effect of doing this would be to remove the language, but not remove it from history.”

Los Angeles County Supervisor Holly J. Mitchell, who introduced a bill to remove “lynching'' from California law when she was a state senator, said the language of the law is important, regardless of its enforcement.

After her grandmother died, Mitchell helped her great-aunt sort out family documents and write a will to protect the Exposition Park home she bought decades earlier.

Mitchell pulled out the deed and was outraged to see language prohibiting black people from living in the home where his family had lived for years.

“I read this and thought, 'Oh my God, this is what I read,'” Mitchell said.

Historian Laura Redford completed her book PhD work at UCLA Regarding racially restrictive covenants in Los Angeles County, he said the earliest he could find real estate agents and developers using restrictive covenants in the county was in 1908. The developer, Lawrence B. Burke, advertised “iron-clad racial restrictions” in about 20 booklets. Block on the south side of Expo Park.

Redford, a visiting assistant professor at Brigham Young University, found in his research that by 1939, 47% of Los Angeles County's residential neighborhoods had “restrictive covenants that prohibited certain racial groups from entering or exiting the community. According to his doctoral thesis, he discovered that

Newsletter

Learn more about LA politics

Sign up for the LA City Hall newsletter for weekly insights, scoops and analysis.

You may receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Conceptually, restrictive covenants exist to outline what owners can do with their property, such as horse stables and other typical restrictions, Ledford said. Stated.

But real estate agents and developers use this system not only to exclude people of color, but also to impose It was also possible to determine the rank of

As a historian, Redford worries that even if restrictive covenant language is removed from land records, history is unlikely to repeat itself in terms of such overt racial restrictions. But he said there were concerns about whether people would understand how these policies separated people. per class.

Mr. Redford said that the Supreme Court stated: 1948 Sherry v. Kramer decisionruled that states that upheld racially restrictive covenants violated the Fourteenth Amendment and that the Fair Housing Act of 1968 outlawed racially discriminatory policies; The court ruled that the issue still remained.

“We continue to segregate by class. We do it by selling by price range…saying, 'This is a community of single-family homes that are worth between this and this.' We can't build apartment buildings,' because that would destroy the value of single-family homes,'' Ledford said. “As a society, we have not done very well in addressing the class discrimination that continues to perpetuate itself.”