At about 1:30 am on September 10, a woman in Rio Rico dialed 911.

Her bedroom door was missing, she told a dispatcher at the Santa Cruz County Sheriff’s Office.

“She believes it was him,” the dispatcher wrote in the report.

In Arizona, a protection order is a specific type of restraining order intended to prevent future acts of domestic violence. Violation of that order is a misdemeanor under state law.

“If that person comes near you, you’re violating judicial process,” said magistrate Emilio Velázquez, who handles petitions for protection orders.

Velasquez said people who have petitioned for protection orders may have already been assaulted by their partners or family members. In other instances, they faced severe and long-term emotional abuse.

And as the COVID-19 pandemic spread, requests for a general restraining order in Santa Cruz County began to surge, Velasquez added.

In 2019, Velázquez told NI that the Nogales Court of Justice received 112 petitions seeking either protective orders or injunctions against harassment.

Subsequently, in 2021, the number of court orders has increased to 256.

As of 2022, the Court of Justice has processed a total of 263 orders of protection and injunctions against harassment.

In an interview last week, Velázquez cited the pandemic as a major factor.

“People spent a lot of time together,” he said. “People’s drinking and drug use increased.”

But Velázquez stressed that court orders can only do so much to protect victims of domestic violence from abuse. He and other experts who spoke with NI pointed out the importance of ancillary resources, ranging from home security systems to victim advocates to emergency safety plans.

“I always say to individuals, ‘When you go ahead and take this order, you have to remember that you must always be aware of your surroundings,'” Velázquez said. Because it can happen.”

Once Velázquez issues a protective order, law enforcement must serve documents to individuals assessed as potential threats.

But according to Anna Harper, vice president and chief strategy officer of the Center for Domestic Violence Control in Tucson, the story usually doesn’t end there.

“There are people who say, ‘Okay, you’ve been in court. Now this order is out. I’m just going to leave you alone,'” she said, adding, “That’s probably a few people. ”

Harper said some individuals with protective orders have instead begged for forgiveness and sought another opportunity for a relationship.

Others are outraged, she said.

“To be told by a judge in court, ‘You don’t do these things,’ is a challenge to their control and power,” Harper added.

In some cases, being subject to a protection order can pose an even greater risk to those seeking safety. She added that it helps determine

“I think…a really honest conversation has to be had with the survivor,” she said. “To really explain, ‘What are the considerations in your situation?'”

Locally, dispatch reports show consistent trends. Santa Cruz County says that at least several times a month, callers contact law enforcement and say their protection orders have been violated.

Accidental Violation and Intentional Violation

A protection order usually prohibits contact between two persons who are facing potential violence and individuals who may commit violence.

But that barrier is easy to break, especially in a small community like Santa Cruz County.

According to county attorney George Silva, when someone violates a protection order, it’s mostly accidental.

“So[the two]just happen to be shopping at Walmart at the same time,” he said. “And it wasn’t meant to be, but the person still reports it. That’s the right thing to do, to report it.”

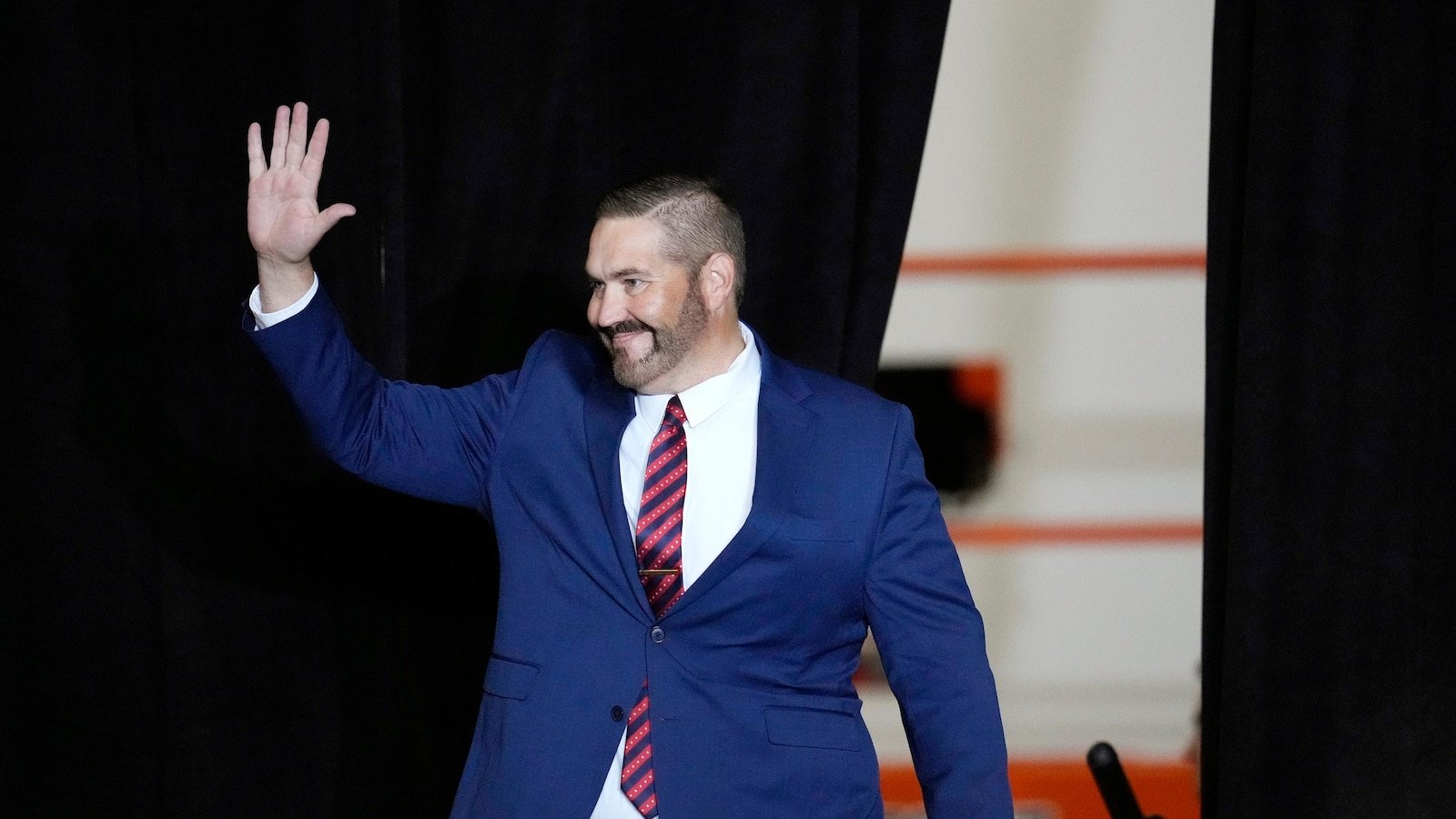

On Nov. 29, Santa Cruz County Attorney George Silva stands for a portrait in his office.

Photo by Angela Gervasi

Silva, whose office investigates and prosecutes violations of protection orders, said these incidental interactions generally do not result in criminal charges.

But in other cases involving more egregious and dangerous violations, the county attorney’s office will seek results.

“We have repeat offenders,” said Silva. “And they’re the people who won’t stop. I mean, I hate to say it like that.

In one instance, a man repeatedly walked past his ex-partner’s workplace and violated a protection order. I chased a woman to her new boyfriend’s house.

In that case, Silva said the man would be charged with aggravated harassment, a felony that could lead to up to two and a half years in prison.

In many cases, when a protection order is issued, the recipient must surrender their weapons. Finding the person’s firearm in violation of the order will allow for more severe prosecutions, Silva said.

“Well, were they going to use that weapon?” he added. “I don’t know, but there are weapons. Things got even worse.”

On December 5, a dispatcher at the Nogales Police Department reported a protection order violation. The two were traveling together, according to NPD.

According to Silva, it’s not uncommon and such violations are difficult to prosecute, he said.

Even after a person has filed a protection order against his ex-spouse or partner, the two may still try to reconcile their relationship. Technically, it’s still against state law to contact you if the order is valid.

“One gets a restraining order and they’re still having a conversation,” Silva said. “And they didn’t mind going out or getting back together and lifting the restraining order.”

As local dispatch reports show, many protection order violations involve children. Individuals can issue protection orders against their ex-girlfriends, but those orders don’t always apply to their children, making shared custody difficult.

In about five months, from July to November, the county attorney’s office prosecuted 11 protection order violations, leading to criminal charges. It’s not entirely clear how many violations were dismissed during the same period. Other cases are still pending, Silva said.

When a violation occurs, law enforcement and prosecutors start looking for evidence.

“Video, witness,” said the sergeant. Oscar Mesta of Nogales Police Department added that officers also usually talk to both parties involved.

“Usually we ask people, ‘Was that on purpose? Did they make any comments about you? Did they touch you?

But finding available evidence can be a formidable challenge, Silva said. Witnesses may be unwilling or afraid to testify.

Technology and social media are making protection order violations even more complex, said Harper of Tucson’s Emerge Center. Individuals can use fake social media accounts and personal phone numbers to stalk and harass her. In her work, Harper has seen survivors of domestic violence receive dozens of blocked calls, often from abusers. I cannot prove that there is

According to Harper, such behavior may not initially attract the attention of law enforcement. More overt acts of violence, such as assault, may naturally take precedence.

However, she said these actions were also alarming.

“More insidious behaviors like stalking, harassment, and abuse like that can actually be linked to very high-risk situations,” she added.

Earlier this year, the NPD faced criticism when a family member called an officer to report a protection order violation. Falsely stated that their situation was civil rather than criminal.

NPD has not explicitly commented on the situation, but Mesta has emphasized in past interviews that officers strive to treat survivors of domestic violence with courtesy.

And while some violations can be difficult to prosecute, Mesta encouraged residents to report suspicious activity. He said the police will answer all calls.

“Say something. Say something,” said Mesta. “I don’t know if the person is slowly progressing to do something else to see if you don’t report it.”

Silva echoed similar encouragement. He said having a paper trail is key to tracking protection order violations.

“I tell my victims, if you go home and turn the flower pot upside down, it could have been the wind,” he added. “But it could have been him, too.”