On a Sunday morning before the big event, Jennifer Liewer stood outside the election center in downtown Phoenix, inspecting the frame of a metal tent that contractors were erecting in the parking lot.

“I told him to go bigger,” she told colleagues. “I don’t know if this is ‘bigger than’.”

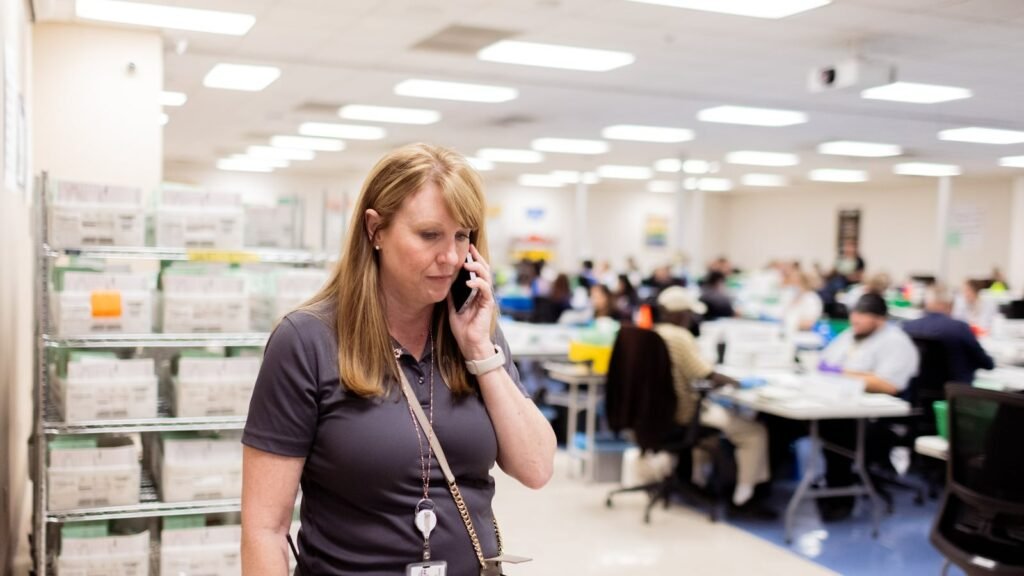

Leewer, Maricopa County’s deputy elections director for public affairs, knows hundreds of journalists from all over the world will be here on Election Day to work in the tent. To do the job then, today you have to be a logistics manager, directing trucks and workers while ensuring voters drive to the ballot box in the parking lot.

County officials were caught off guard when global media attention focused on Maricopa during the past two federal elections. Journalists watch as President Donald Trump’s allies recount all 2.1 million votes cast in the county since 2020, after Trump claimed without evidence that the election was stolen. arrived for. And on the day of the midterm elections, Widespread technical failures at polling stations similarly spurred allegation of fraudthis time from unsuccessful Republican gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake.

Trump and Lake are back on the ballot this year. Arizona, especially Maricopa, the nation’s largest battleground state, was expected to determine the outcome of the presidential election. Nearly 700 journalists applied for certification. Liewer and his colleagues recognized this as an opportunity to restore public confidence in elections in one of the most closely watched and most closely scrutinized counties in the state.

The county added staff to respond to media requests, sent reporters a packet in advance detailing how the county would conduct elections, and prepared reports. Live fact check page The website requires journalists working from election center tents to obtain credentials and spent $35,000 to install media tents and restrooms in the parking lot.

Liewer allowed VoteBeat to interview her in the days leading up to Election Day.

On Sunday, while meeting with colleague Ali Flahib in a room that served as a communications command center, her cell phone rang repeatedly. Soon, everyone responsible for campaign messaging will be sitting at a row of tables with computer monitors. Two projector screens at the front of the room will soon display wait times at polling places and an updated list of pending media inquiries. On the wall was a framed black-and-white sign with a quote from Scott Jarrett, one of the county’s two election officials.

“This is the Super Bowl of elections,” one said.

“We are the beauties of the ball,” declared another.

County officials didn’t ask for this kind of attention, but they’re getting used to it.

‘Shut down the noise!’ Maricopa County officials fight back

In 2020 and 2022, Liewer watched from behind the scenes as a spokesperson for the county attorney’s office. When she took on the role last year, she knew what she was getting into.

This wasn’t her first high-pressure role, and she often responded to crises. Fresh out of college, she started working for the American Red Cross in Phoenix and was called to New York after the 9/11 attacks. She served as Glendale’s spokesperson for the city when it hosted the Super Bowl in 2008, responding to high media interest in its financial issues, and later served as Glendale’s spokesperson for Arizona when its elected county attorney faced disciplinary proceedings. Served as spokesperson for the Supreme Court. She joined the county attorney’s office under Alistair Adell in 2019, where the office represented Adell as he publicly battled alcoholism.

And she was there in 2022 when the office commissioned an outside investigation into Election Day issues. When the communications role started the following year, she knew she could handle it.

“Here we are all in this together and the chaos is on the outside,” she said, sitting in her office on the Sunday before the election. It’s no surprise to her that Jarrett is now coordinating media arrangements and messages for what she calls the “Super Bowl of elections,” when she once did the same thing for the actual Super Bowl. Unforgettable. Of course, the stakes in a presidential election are a little different.

She has watched county election officials manage all the twists and turns of the past four years. She then uses that information to predict what will happen to her.

Supervisor Bill Gates said the county had been taking a “reactive approach” to communications for some time. That was true even when state Senate Republicans subpoenaed every vote cast in the 2020 county elections in a purported audit.

However, the strategy soon changed.

In May 2021, CyberNinja, a Senate contractor, falsely accused county officials. Election file deletion. County Recorder Stephen Richer, a Republican, had previously been modest, but when Trump repeated that false claim on social media, he said: Richer responded on Twitter, calling it “unstable.”” Around that time, Jack Sellers (Republican), the usually mild-mannered Supervisory Board Chairman, He began calling the audit “regrettable.””

Since then, the mood of the county has changed.

“We thought, ‘Enough is enough.’ We can’t continue to be silent,” Gates recalled. “That’s been my motivation ever since. It’s about protecting the team and protecting the employees.”

County communications director Fields Moseley has begun transforming the county’s boring social media accounts with live fact-checking and a little bit of sarcasm for auditors.

“#RealAuditorsDont: Think you’re guilty and post false information like it’s a Season 1 cliffhanger.” Account that tweeted May 14, 2021.

It was a way for them to “cut through the noise,” said Zach Shira, Gates’ chief of staff at the time and now the assistant county manager overseeing elections. “There was no other answer.”

2022 Midterm Elections: Election Day Setbacks

As the 2022 midterm elections approach, the county adopted a COVID-19 response strategy and established a command center for the first time.

A draft county communications plan at the time stated that “immediacy is a primary concern.” “Rumors and misinformation must be addressed as soon as possible.”

Prior to the election, county officials held weekly press conferences. And once voting began on Election Day, counties found themselves facing a significant problem. Counters in the county were not accepting ballots, and county officials had to tell reporters they didn’t know why.

That night, reporters packed the lobby of the election center and questioned officials. Officials said the problem was with the ballot printing machines, not the counting machines, but did not provide details that night or for months. I’m forgiven for not being able to answer right away. conspiracy theory To prosper.

Voter confidence took another hit.

After that, the county began to push for more public tours of election centers to strengthen that. Officials have hosted about 100 tours between elections so far this year alone. The county spent $1.8 million this year on pay TV, radio, digital and social media ads and billboards to bring information about voter registration, mail-in voting and other issues directly to voters before the election.

decide what to say and what not to say

Behind Liewer’s desk is a sign that says, “Do what’s right, not what’s easy.”

When under pressure, she said, it’s important to be honest about what’s going on while respecting your team’s opinions about information you’re not ready to share. If you can’t talk about something, speak up about it, she said.

“I think it’s important to not only be honest with the people you work with directly, but also be honest with the community,” she said.

Of course, not everyone agrees on “what is right” or whether the county has been doing its communication efforts correctly thus far.

Sometimes the county withholds information. Officials won’t answer cyber ninja questions about 2020 election, wait 5 months for detailed answers on what happened to ballot printing machines after 2022 until independent investigation completes selected. In both cases, misinformation spread without prompt official response.

Critics also took aim at the county’s past requests for social media platforms to remove posts that officials determined were false or harassing. And after the county began restricting events to accredited media, the court ruled against media outlets the county had banned, including Gateway Pundit, a right-wing website that frequently publishes misinformation. The court ruled that access must be provided. Liewer must take all of this into consideration.

‘No whack-a-mole’: authorities draw up plan

On the Monday morning before the election, Liewer sits at her desk, talking to a local KTAR radio reporter. She has been fielding media requests all morning and can’t wait to get off the phone. She still has several hours to complete preparations for her last of three press conferences before the election. Dozens of journalists are expected to attend. She told the reporter she had to go.

“I wish I had been kind,” she said as she hung up.

She reads the printed script, highlighting certain comments and crossing out others.

Some reporters have been asking her about the county’s delays in processing early voting. A local Axios Phoenix reporter texted her and asked exactly what the results would be at 8 p.m. on election night. Are they all early votes received by Friday or Saturday?

“Actually, it’s neither,” Liewer says, dictating a text message on her cell phone. “The Recorder will speak on this matter at a press conference this afternoon.”

Mr. Flahive stopped by to let the staff know that they had started a new spreadsheet. This is to track requests for live shots on Election Day by news broadcasters. They’re trying to work through a backlog in their media inbox, but requests are coming in faster than they can respond. Overall, the team of seven will respond to more than 1,000 media inquiries from September to mid-November.

In the afternoon, more than 100 journalists sit at tables or stand behind cameras on tripods in the county conference room. Gateway Pundit employees who were evicted in 2022 are in the front row.

Gates, Richa, Shira, and Leewa walk forward. of the room. Mr. Moseley, the county communications director, is already in the back.

Mr. Shira concluded his speech by telling the audience that he would “not play whack-a-mole” despite misinformation on election day.

“But what we take very seriously is any misinformation that impacts a voter’s ability to vote,” Sila said. “We’re going to be very aggressive in reporting on that misinformation.”

Liewer sets the stage for what visiting reporters can expect. “Obviously, we have a lot of members of the press here,” she told the crowd. She says her staff won’t be able to answer everyone’s questions, but will be there all week to help.

So she opens it to the floor.