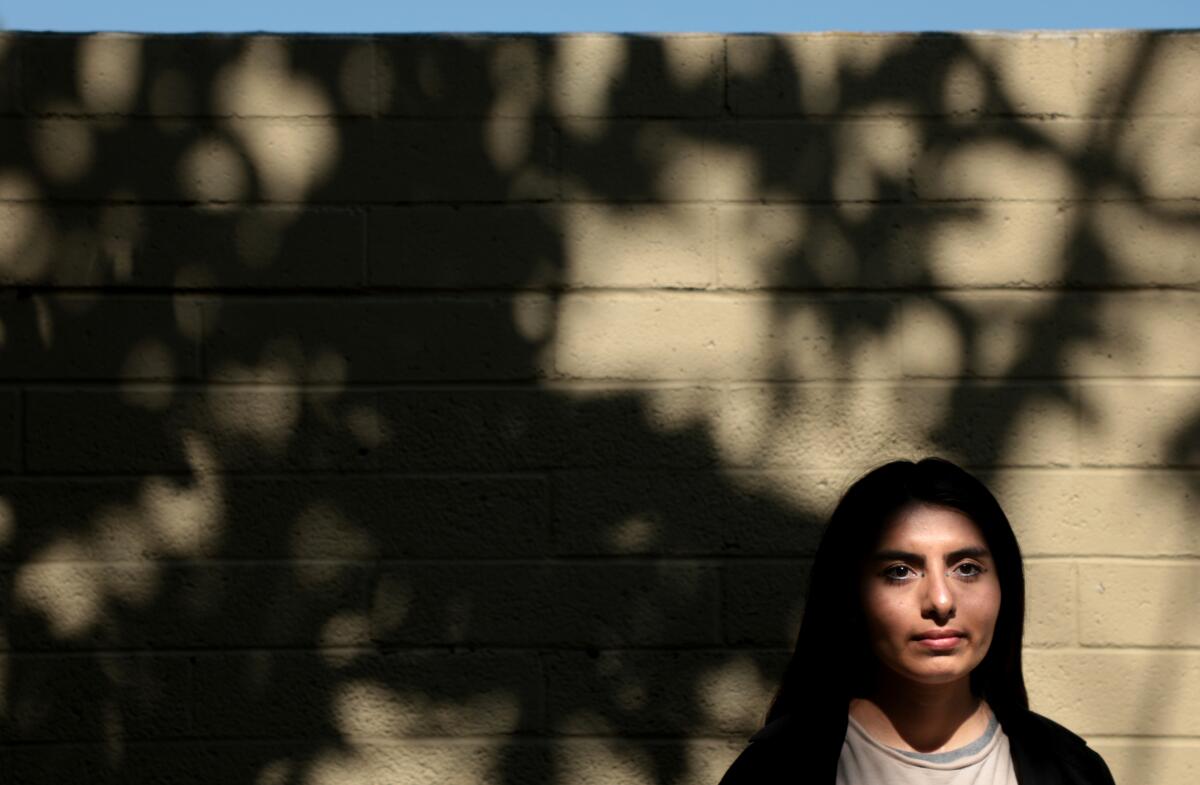

Iziko Calderon was in 10th grade when the seizures began.

A foster child who had bounced around from one abusive home to another, Calderon believed the incidents were a reaction to years of pent-up trauma: He would sometimes collapse at school, writhing in pain from nerve pain as if on fire.

“Everyone at school was afraid of me,” recalled Calderon, now 22 and a community activist.

Calderon, who uses the pronoun “they,” dropped out of Los Angeles High School that school year when he was about 16, in part because his teachers didn't know how to handle the debilitating events.

Two years later, just after turning 18, Calderon again fled his stressful living situation and returned to school—not to enroll, but to sleep outside on a park bench. They spent the next year homeless, sleeping in their cars and showering on Venice Beach, all while in the custody of the Los Angeles County Department of Children and Family Services, Calderon said.

Every year, teenagers slip out of foster homes and onto the streets, but the county is responsible for protecting them. County officials have promised safer, more reliable placement options for older foster children for years, but a sweeping federal lawsuit is putting new pressure on the nation's largest child welfare system to make good on that promise.

In June, U.S. District Judge John Kronstadt Class action lawsuit They urged Los Angeles County and the state to move forward, emphasizing that the government's responsibility for foster children does not necessarily end when they turn 18.

In California, teenagers can choose to remain in foster care until they turn 21, meaning the government is responsible for keeping a roof over their heads throughout their early adulthood. The four law firms suing the state and county — Children's Rights, Public Counsel, Munger, Tolles & Olson, and Alliance for Children's Rights — argue that this promise rings hollow because older foster children lack stable housing and mental health services.

“There are still too many kids living on the streets, couch surfing, or in and out of homeless shelters.” Lecia Welch“This is incredibly dangerous,” said the deputy director of litigation at a New York-based children's rights group.

Former foster child Iziko talks with best friends Christina Gregorio, left, and Pablo in a park in Los Angeles. Lawyers suing Los Angeles County allege the county has failed to provide adequate housing for older foster youth who choose to remain in county custody until they turn 21.

(Wally Scalisi/Los Angeles Times)

Last week, the lawyers filed an updated complaint that provided new details about one of their allegations: that neither the counties that run foster care programs nor the state, which oversees them, know how many foster youth are living on the streets.

“It's very hard to compare Los Angeles to other places because we don't track whether kids are becoming homeless,” Welch said.

The lawyers say DCFS officials told them the county doesn't track homelessness rates among foster youth. Neither does the California Department of Social Services. The lawsuit cites the department's principal deputy commissioner as telling lawmakers in April that “the agency does not track data in a way that would allow it to know how often it tracks homeless youth.” [foster] Young people are experiencing homelessness and housing insecurity.”

about 2,500 young people The children are between the ages of 18 and 21 and are in the Los Angeles County foster care system. DCFS did not respond to The Times' questions about how many are homeless and stressed that it does not comment on pending litigation.

“The county is committed to ensuring the well-being of young people as they enter adulthood and providing available services to assist with that transition,” officials said in a statement.

The state Department of Human Services said officials do not comment on ongoing litigation.

The county's most recent homeless census found 3,718 young people between the ages of 18 and 24 living in temporary housing or on the streets.

“I wouldn't be surprised if close to half are in our system,” Superintendent Katherine Burger said, adding that she recently met with DCFS Director Brandon Nichols about the possibility of master lease units for teenagers in foster care.

Former foster child Iziko poses in a park in Los Angeles.

(Wally Scalisi/Los Angeles Times)

Calderon, soft-spoken, with shaky knees and scuffed Converse sneakers, could become the “face” of a lawsuit pending in federal court.

Like many foster children, Calderon recalls a childhood marked by violence. DCFS took them from their parents when they were babies after allegations of abuse at home, Calderon said. A series of difficult upbringings followed, including a period when Calderon was returned to her father, who she said took them to his native Peru when she was a teenager, deriding child welfare agencies for not helping them.

At age 15, Calderon returned to the United States on his own, and the seizures soon began again: After a severe attack on the way home from gym class, Calderon was sent to a psychiatric hospital and placed back under DCFS supervision, according to the complaint.

At the time, Calderon was living with her sister, who lived near the school, but the attacks were disrupting her sister's stability and tensions were building. Calderon asked a social worker to help her find a new place to live.

Older foster children have two main housing options: The county either provides an allowance they can use to find housing on the open market, or offers free, supervised housing, often along with a suite of services to help them take their first steps toward adulthood, including counseling, job-hunting assistance and budgeting tips.

Calderon said social workers had submitted two applications for supportive housing, but no progress had been made before Calderon headed to the park bench.

“She was in a state of panic,” Calderon said. “I was always like, [ask] “I ask her if there's anything I can do for her. The worst part is when you ask for help and the caseworker says, 'I don't know.'”

Supported housing is seen as a kind of holy grail for older foster children, whose wait times can stretch for months, as they struggle in the rental market with no rental history, no guarantors and monthly allowances of just over $1,200.

Calderon, who received benefits when he was homeless, said he applied twice for a studio apartment but was rejected.

Without enough foster housing, counties sometimes rent hotel rooms for older foster children with little oversight. the Investigative Journalism Program at the University of California, Berkeley; It found that the county housed hundreds of foster children in hotel rooms between January 2022 and May 2023, including young people in urgent need of mental health care.

In February, the state ordered the county to “immediately cease” caring for foster children in hotels, saying such facilities were not licensed to care for foster children.

DCFS told The Times that it is no longer using hotels for temporary housing.

Michael Nash, a former presiding judge of Los Angeles County's juvenile court, believes the county needs to focus on finding nurturing, stable placements for foster children — ideally with families — before they turn 18. Once they're past 18, he says, there “will never be enough” housing to help them all.

“We have thousands of kids who could be aged out of our system,” he said. “What does that mean for the homeless population? It's not good.”